The Fitzherbert family were a Norman family who came to England at the time of the Norman Conquest and were staunchly Roman Catholic.

Sir Anthony Fitzherbert of Norbury, Derbyshire, was born c.1470 during the year-long second period of King Henry VI’s reign. During the turbulent times of the War of the Roses he was to live under the reigns of five kings, sometimes from the Yorkist and sometimes the Lancastrian houses. It was not their fealty to the Yorkists that was to be the downfall of the Fitzherbert family under the Tudors, but their ‘stubborn’ adherence to the Church of Rome.

It is thought that Anthony was educated at Oxford, but no concrete evidence of this exists; nor is it known at which of the Inns of Court he received his legal training, though he is included in a list of Gray’s Inn readers. He became one of England’s most learned judges. In Henry VIII’s reign he was called to the degree of Serjeant-at-Law, c.1510, and six years later he was knighted and appointed King’s Serjeant. In 1522 he was made one of the Justices of the Common Pleas, equivalent to a High Court judge today. He was considered one of the most notable legal writers of the 16th century, producing many of the most authoritative and enduring English law books for practitioners and students alike.

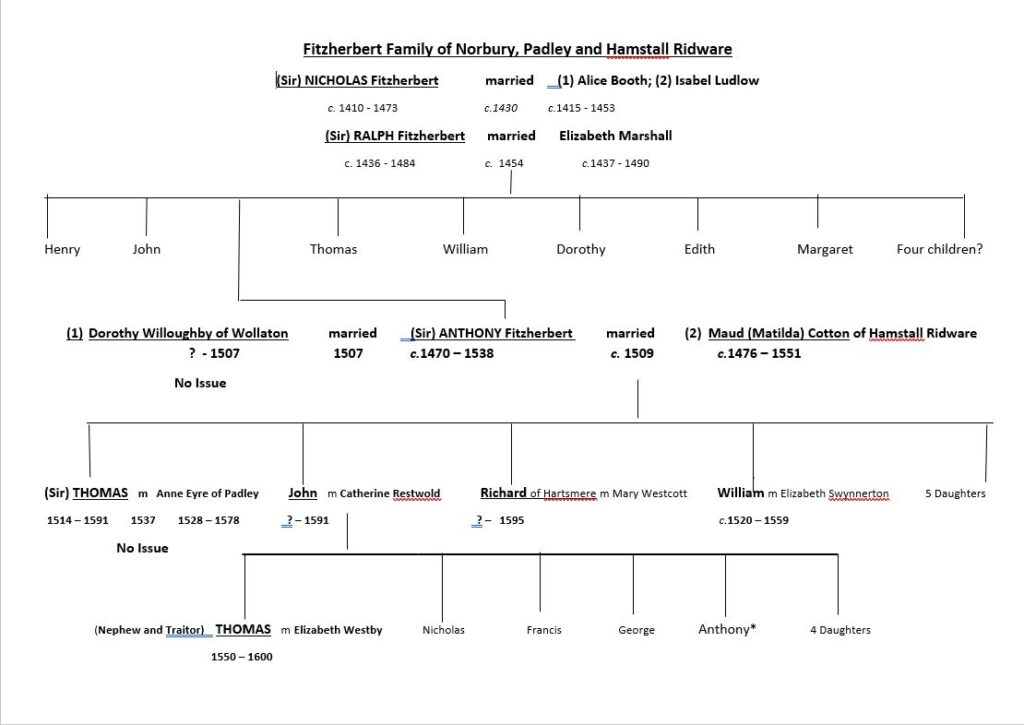

In 1507 Sir Anthony married Dorothy Willoughby of Wollaton, Nottingham; however, she died childless in November of that same year. Secondly, he married Maud, or Matilda Cotton and thus the manor of Hamstall Ridware passed to the Fitzherberts of Norbury as there were no surviving male heirs of the Cotton family. There is no evidence that they ever lived at Hamstall Hall, but during Sir Anthony’s lifetime, the people of Hamstall Ridware would have glimpsed the larger world beyond its borders, because of his work within the London courts, and benefitted from Sir Anthony’s largesse. He and Maud had several children, in some accounts five boys and five girls, although the precise number is not known as there were some who died in infancy.

Sir Anthony was now a man of some importance in King Henry VIII’s court, but over time he became increasingly uncomfortable with the direction Henry was taking towards a break with Rome and strongly disapproved of the ecclesiastical policy, particularly the suppression, destruction and acquisition of the monasteries. Dr J. Charles Cox wrote: ‘Sir Anthony Fitzherbert was considered a great lawyer of his day…He is said to be the only man who dared to rebuke, not only Cardinal Wolsey, but even the King himself on the subject of the alienation of church lands’. But as far as Dom. Bede Camm, an English Benedictine monk and author of many works on Catholic martyrs was concerned, ‘We have to own with regret that, as a Catholic, he did not take that firm position which brought such immortal glory on Sir Thomas More’ (i.e. martyrdom). It could be argued that despite his misgivings, it was as an act of self-preservation, that he agreed, albeit unwillingly, to be one of the 15 commissioners who sat on the tribunal which tried and convicted Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher of treason in 1534. Then he was appointed to the Special Commission that presided over the trial of Anne Boleyn in 1536. Although the final establishment of the Church of England was still 21 years away, on his deathbed in 1538, it is said that he exhorted his children never to accept church lands and remain true to the Catholic faith. The promise was kept, but two of his sons and possibly a third, paid dearly for it with their lives. Apart from the expected family bequests, Sir Anthony did not neglect his wider responsibilities. His will included bequests and instructions with regard to Hamstall Ridware, stating that his male heirs should:

Find a priest forever at Norbury and Ridware to pray for us and our ancestors forever and our successors, and I have left them lands enough for that intent, and if they perform this intent, I doubt not but that the heirs males of Fitzherbert shall the lenge [long] continue; And if they can, amortise two chantries in those two churches…the other at Ridware according to my mind in Jesus’ chapel there; And I will that every of the said chantry priests have four marks and meat and drink for their stipend; And to every of my godchildren in Ridware 3s 4d…

The next generation of Sir Anthony and Dame Maud’s family were to live in even more precarious times than their parents during the reigns of four Tudor monarchs with opposing religious beliefs; firstly Henry VIII, then strongly Protestant Edward VI, zealous Catholic Mary I and finally Protestant Elizabeth I.

It was their eldest surviving son, Thomas, who had the strongest links locally. He was born between c 1511 – 1517. He married Anne Eyre, daughter and heiress of Sir Arthur Eyre and Margaret Plumpton-Eyre, another strongly Catholic family. Their marriage settlement is dated 20 October 1535 and by marrying Anne, Thomas added the Padley estates in Derbyshire to his possessions, although he passed the tenancy to his brother John who lived there with his family. Sir Thomas had inherited Norbury from his father, Sir Anthony Fitzherbert in 1538, which is where he resided, and Hamstall Ridware manor in Staffordshire, from his mother, Maud, in 1551. Thomas and Anne had no children and this was to be the cause of ‘the great family tragedy’.

Although not born into an aristocratic family, Thomas fared well under Henry VIII and attained various positions of honour. He was appointed to the office of Sheriff of Staffordshire twice. The first time was in 1543 and the second in 1546 and he was also appointed a member of the last parliament of Henry VIII, from 1545–1547.

Thomas was dubbed a ‘carpet knight’ on 22 February 1547 by Edward VI on the day after his coronation. (A carpet knight was one who was dubbed when kneeling before the monarch indoors for good service to the crown rather than on the battlefield for valour.) Thomas’s continued employment in the reign of the Protestant king implied that he was as capable of adjusting to change as his father had been. As Dom Bede Camm, an English Benedictine Monk, wrote:

He was even appointed one of the Commissioners to take survey and inventory of Church goods and ornaments in the Hundreds of Offlow and Pirehill and in the Lichfield Chapel Acts he was recorded as one of the Commissioners [for Staffordshire] who took from the Ministers of that Church an inventory of the jewels and vestments etc. and sold them, placing the best jewels and vestments under the seal of the King. This must have been a most repugnant act of sacrilege to Thomas.

He may even have had to visit Hamstall Ridware’s neighbouring parish. Frederick William Hackwood, writing the ‘Chronicles of Cannock Chase’ in the Lichfield Mercury of 1903, notes that in the Return of the Commissioners in 1552, one of the churches visited was that of Pipe Ridware, where it was recorded that the ‘chalice had a silver bowl on a tin foot’ (see Appendix 1).

Edward’s reign lasted a mere six years and Thomas might have been forgiven for thinking that life was now going to stabilise and even improve. Had the staunch Catholic Mary’s reign lasted longer, he and the Fitzherbert family’s future would surely have been secure. He was appointed High Sheriff of Stafford for the third time in 1554. However, Mary’s reign was even shorter than Edward’s and she died in 1558. It was with the accession of Elizabeth I to the throne that the Fitzherbert family’s fortunes changed dramatically for the worse.

When Elizabeth came to the throne in 1558 she inherited a still predominantly Catholic country. Her personal religious convictions have been much debated by scholars. Outwardly she was a Protestant, but kept Catholic symbols, such as the crucifix and rituals, which she enjoyed. For a time she tried to tread a middle path and displayed a degree of religious tolerance. However, eventually she had as many Catholics executed as Mary had burned Protestants, and by the end of her reign England was firmly an Anglican country.

In 1559, the first year of her reign, an Act of Parliament was passed for ‘Restoring to the Crown the antient jurisdiction over the estate ecclesiastical and spiritual’. Everyone of any rank or position had to take the Oath of Supremacy acknowledging her position as Supreme Governor of the Church of England and renouncing any other spiritual or ecclesiastical authority. To anyone refusing to take the oath, the penalty was loss of all offices and civil rights. At the same time the Act of Uniformity made the Book of Common Prayer the only authorised manual of worship, prohibited any other Catholic rites and meant that the Holy Sacrament of Mass had become a crime and those who refused to attend services of the Church of England were thereby committing the statutory offence of recusancy. Sir Thomas could not in all conscience take the Oath nor agree to the Act of Uniformity although his fealty to Elizabeth as head of state was never in question.

In its literal sense recusant means a person who refuses to submit to an authority or to comply with a regulation. In its historical setting, it applies to those who maintained an attachment to the Roman Catholic Church and who refused to attend Anglican services. Sir Thomas Fitzherbert could not in all conscience swear these oaths. For those who decided to stand firm and suffer the penalties, there immediately arose the necessity to procure the services of a priest to say Mass and administer Sacraments and a place in which to do this. All had to be done in the utmost secrecy. Catholicism became an ‘in-house’ religion, literally. Hamstall Hall was one such house.

The Recusancy Laws specifically targeted Roman Catholics who were referred to as ‘Popish Recusants’. It was the 14th clause of the act that was particularly harsh on the ordinary people. Any person not resorting to the now Anglican Church on Sundays or holy days was to forfeit 12 pence for every service missed, a considerable amount of money in those days. Dissent was outlawed and as a result Sir Thomas Fitzherbert had the honour to be one of the first victims of these detestable laws. Recusants everywhere were harassed by fines, forfeitures and imprisonment in order to compel the attendance at church.

Dr J. Charles Cox, a member of the Anglican clergy, writes:

Where the local magistrates were deemed lax in their efforts, Special Commissioners, armed with the fullest powers immediately from the Crown – powers, which in their full use of torture, as well as other respects, more closely resembled the Inquisition than anything hitherto established in England, visited the disaffected districts.

This persecution was particularly severe between 1561 and 1563, notably in Derbyshire and Staffordshire, with Hamstall Ridware, under the governance of their Lord of the Manor, Sir Thomas Fitzherbert, being regarded as a ‘hotbed of disobedience’. At least 30 of his household and tenants were to suffer harsh punishments, either monetary or deprivation of liberty for their adherence to their faith.

Having repeatedly refused the Oath of Supremacy, which would have forced him acknowledge Queen Elizabeth as the Supreme Head of the Protestant Church and renounce his Catholic faith, Sir Thomas was arrested in 1561, and imprisoned in the Fleet Prison, London. Thus, he had little chance of enjoying life in his Staffordshire manor of Hamstall Ridware and spent most of the next 30 years, in one form of imprisonment or another, being dragged from prison to prison, first in the Fleet, then the county gaol at Derby, then Lambeth Palace, Broughton Castle near Banbury and finally the Tower of London, with only three short intervals of freedom.

During this time Father Hugh Hall, a Marian priest (that is a priest who was ordained during the reign of Queen Mary), was the incumbent at the Hamstall Ridware Church of St Michael and All Angels, but he was deprived of his living in 1562 after Sir Thomas’s removal in 1561. Through the secretive Catholic Network he was enabled to get away and was sheltered at Park Hall, Castle Bromwich in Warwickshire, home of Edward Arden who was sheriff of Warwickshire. This was another staunchly Catholic family. In order to avoid being discovered he was disguised as a gardener, but eventually the whole household, including Edward’s wife Mary, was captured in 1583 and sentenced to death. Edward Arden was hanged, drawn and quartered for his faith but remarkably, Father Hall was reprieved before execution. It is possible that he was spared because he confessed – either actually or allegedly – names of other Catholics in the county during his ‘examination’. He escaped to the continent.

In 1572 the Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, when French Catholics massacred French Protestants, caused panic in England. This and various plots to overthrow Elizabeth and put Catholic Mary Queen of Scots on the throne led to a tightening of the recusancy laws and increased punishments. Now all people who held or attended private masses were to be imprisoned. Where recusants had been fined 12 pence for each non-attendance at the Church of England services, this was increased to a massive 20 shillings a month and non-payment resulted in imprisonment.

Naturally confinement had a detrimental effect on Sir Thomas’s health and at a meeting of the Privy Council, on 2 May 1574, a letter was sent to the Archbishop of Canterbury: ‘To use his discretion upon a suit made for the “enlargement” of Sir Thomas Fitzherbert for two months, in respect of his sickness, and disposing of his lands and goods.’ The latter motive was probably the more effective with the Council, because even an imprisoned knight had to pay the sum of 8s. 6d. for his weekly commons and wine, besides 25s. 4d. a week for his room and also still had to pay the crushing fines levied on recusants, so if he was ‘enlarged’ from time to time, it was chiefly that he might find the means of raising this money by the sale of lands or goods. It does not appear that his wife, Anne Lady Fitzherbert, suffered any penalties, even though until her death in 1576, she had continued to harbour Marian priests and protected Catholic tenants and servants at both the Norbury and Hamstall Ridware estates. This was probably due to the fact that early on in Elizabeth’s reign, it was considered that as married women controlled no property in their own right, it was ineffective to fine them as they were unlikely to be able to pay the penalty. This thinking did not apply to widows or spinsters. When the laws were made more stringent, at least five married women from Hamstall Ridware suffered under the Recusancy Law. After Lady Anne’s death her brother-in-law, John Fitzherbert of Padbury took on the roles she had undertaken until his arrest in 1588.

There was increasing concern that too many people were flouting the new laws, so in 1577 the Privy Council required the bishops to make returns of recusants in their dioceses. Having made a return in November, Bishop Thomas Bentham of Coventry and Lichfield followed it with a more detailed return for Staffordshire in February 1578. It is notable that the place with the highest number listed was Hamstall Ridware. Besides Sir Thomas and two members of his family and their five servants, 33 recusants, all tenants or servants, were listed, including Martin Audley, Sir Thomas’s faithful body servant, a native of Hamstall Ridware.

Also in 1578, on 1 April, Sir Thomas, being then a childless widower, made settlement of the manors of Norbury, Padbury, Hamstall Ridware, and his other property, on his nephew, Thomas Fitzherbert, on the occasion of his marriage to Elizabeth Westby, daughter of John Westby of Mowbrick, Lancaster. The lands:

…were settled to the use of Sir Thomas for life, remainder to his brother John Fitzherbert, father of said nephew, for life; remainder to his younger brother, Richard Fitzherbert of Hartsmere; remainder to Thomas jnr. and his heirs male by Elizabeth Westby…

In the words of Dom Bede Camm:

But now the great tragedy of Sir Thomas’ life was about to overwhelm him. The story is a very terrible one. ‘Have I not chosen you twelve and one of you is a devil’ – these words of our Blessed Lord seem to ring in one’s ears, as one studies the story of the Fitzherberts.

Thomas Fitzherbert (the nephew) was the traitorous Judas or devil. Probably at the time when he himself was imprisoned in Derby gaol for recusancy in 1583, he fell into the hands of one of the most feared and hated men of that time, Richard Topcliffe, the priest-catcher. No doubt in return for his release, Thomas was ‘persuaded’ by Topcliffe into conforming to the Church of England and ‘encouraged’ to turn informer on his family and neighbours. In the estimation of Camm, Topcliffe was nothing short of evil:

Topcliffe the ‘detestable scoundrel’ persuaded him [Thomas] to plot against the life of his father, John and his uncle Sir Thomas, in order that he [Thomas] might retain their estates. Topcliffe persuaded him that if he did not take speedy steps the whole property would be forfeited for recusancy so that he would never enjoy it.

Being made aware of this collusion, Sir Thomas sought to take legal steps in order to deprive his nephew Thomas of the inheritance settled on him at the time of his marriage. Eventually Sir Thomas conveyed to his brother Richard, of Hartsmere, ‘all his manors and estates in trust’, only to have Archbishop John Whitgift, a strong supporter of Protestantism, nullify the new will. (Hartsmere was called ‘an estate in Staffordshire’ belonging to Sir Thomas. This was probably Hartsmere at Hamstall Ridware).

Camm continued:

The treachery was the more horrible, as Sir Thomas had brought up his nephew from childhood as his heir, and ‘loaded him with every kindness’. But Topcliffe knew how to terrify by his threats as well as to fawn and cajole, and no doubt the wretched young man had somehow put himself in the villain’s power: At any rate, we know by the miserable young man’s own avowal that he ‘entered into a bond whereby Topcliffe would be rewarded with the gift of the Padley Estate and £3,000’ thus giving up his uncle and bringing forward the day when the young Thomas could enjoy his considerable inheritance.

By August 1586, Sir Thomas was at Norbury, very sick.

Furthermore, wrote Camm:

The horrors of a long imprisonment in Elizabethan days are better imagined than described. No wonder that the poor old man, now nearing three score years and ten, should have been very weak and indisposed in bodie, not able to travel as yet without further danger of his person. He was therefore graciously permitted by my Lords of the Council to remain at any of his houses either in Derbyshire or Staffordshire for the space of three months without breach of his bond wherein he standeth bound to the Queen’s Majesty.

This bond had been dated 17 January 1585. He next presented himself before the Council on 4 February 1587. In all he had had just a year of comparative liberty.

Yet despite all his deprivations, Sir Thomas was “so loyal to Elizabeth in matters temporal, that not-withstanding the heavy and repeated fines to which he had been subjected, he had volunteered to supply double the contribution demanded of his estate on the approach of the Armada.”

After the defeat of the Armada in 1588, measures against recusants were again intensified and some of these were felt by many of the inhabitants of Hamstall Ridware, and especially Marian priests who were sheltered or ‘harbored’ by the Fitzherbert family. One was Thomas Collier – deprived as vicar of Uppingham in Rutland who came and secured Bancroft farm in Hamstall Ridware in 1560. He was still there and convicted of recusancy in 1585, but was a supposed fugitive in 1589. Walter Barlow, another priest, chaplain to the Fitzherberts, was imprisoned in the Marshalsea prison in 1582 and then Stafford gaol in 1586. In 1589 Agnes Knowles, a widow, had goods and two-thirds of her land seized, while two labourers and two husbandmen also had their goods seized. These recusants and others in Hamstall Ridware were all recorded in the Exchequer Pipe Rolls of 1581–1592 (see Appendix 2). For about nine months from March 1589 to early 1590, Sir Thomas was incarcerated at Broughton Castle, near Banbury before being sent back to the Tower of London.

Topcliffe thought that Staffordshire recusants had been ‘winked at with the connivance of the Clerk of the Peace of Staffordshire, that lewd fellow Nicholas Blackwell.’ Even though he was involved in some of the Staffordshire tenants of the Fitzherbert family being apprehended, some of them dying in the county gaol. However, Topcliffe’s suspicion of leniency might have had some justification. Blackwell lived in Hamstall Ridware and he was himself once suspected of recusancy. To that end he was examined by the Privy Council in 1588 on several counts of devising ruses that enabled his neighbours there to escape the full force of the law, all of which he denied although he apparently agreed that he had used his influence with the Sheriff to try to secure their release. Interestingly, although he claimed not to be a recusant, he admitted that his wife had been one before and since their marriage. Yet neither of them appear to have been censured in any way as can be assumed from the contents his will held at Derbyshire Record Office:

Will and probate of Nicholas Blackwell of Hampstall Ridware (Co. Staffs) Gentleman.

All his lands, tenements etc. to his wife Senche for her life, with remainder to Thomas Eyre and his wife, Prudence, daughter of Nicholas; he also leaves his wife his goods and chattels for life, with remainder as above to whom he also leaves several horses (specified); to Rachaell Slefeild 20 marks and to George Blackwall, son of his brother Hugh, £10. 28th January, 1598/9.

As a local, perhaps his usefulness outweighed his ‘sins’; indeed, he was instrumental in capturing Richard Fitzherbert and other Hamstall Ridware recusants including, ‘Thomas Capon, keeper of Sir Thomas’ park at Ridway (Ridware)’, in 1590.

The net was also tightening around the wider Fitzherbert family including that of Sir Thomas’s brother, John Fitzherbert of Padley. Though being Catholic was not illegal, it was illegal to be a priest and a treasonable activity to harbour them.

Cox wrote:

That wretched family traitor, the young Thomas Fitzherbert, actually betrayed his own father, by sending the Earl of Shrewsbury, [the Lord Lieutenant of Staffordshire] word as to the day and hour when he would be found. The lighting on the two priests seems to have been accidental.

John, two of his other sons and two priests were captured there and incarcerated in 1588. They became known as the ‘Padley Martyrs’, but that is another story. John Fitzherbert was reprieved of the death sentence for harbouring priests, by an alleged payment of £10,000 in bribes and he died a ‘natural death’ in the Fleet in 1590

When Sir Thomas was first imprisoned by the Commissioners in 1561, his younger brother Richard, Sir Anthony’s third surviving son, escaped to the Continent and was outlawed.

He returned secretly c.1583 and resided at Norbury Manor for a number of years until spies reported the fugitive’s whereabouts c.1590, and the Privy Council despatched one Edward Thorne, a ‘priest hunter’ or pursuivant, to effect his capture at Norbury. From the Privy Council Papers it can be seen that Thorne was no stranger to Richard Fitzherbert. He had already dispossessed him of the estates of Hartsmere and Bancroft, part of the estate at Hamstall Ridware and carried off all his cattle, in spite of Sir Thomas’ protests in 1589. These seized lands were let by the Crown to Thorne from 22 December 1591. No more is heard of Richard and it is presumed that he too, died in prison, possibly on 9 June 1595.

Acting on Thomas the younger’s insinuations regarding his uncle, Sir Thomas, there followed active efforts to find grounds on which to incriminate him in treasonable practice with which he could be charged. The written charges or ‘Interrogatories’, drawn up by Topcliffe, contained assertions that sought to involve Sir Thomas in the Rising of the North, as far back as 1569, even though he was incarcerated at that time, as well as in Babington’s conspiracy of 1586, both with the intention of having Catholic Mary Queen of Scots put on the throne of England.

It was hoped that valuable evidence in his trial would be given by Richard Arnold (alias Audley), a young priest and son of Hamstall Ridware tenants; Sir Thomas’s faithful body servant; Alice Royston, the housekeeper at Norbury; Thomas Coxon, the keeper of his park at Hamstall Ridware; and his bailiff and other tenants. His brother Richard Fitzherbert was top of the witness list. In all there were about twenty witnesses named, all of whom were relatives or tenants of Sir Thomas, and all prosecuted for recusancy. It was not likely, as Dr. Cox remarked, “that much could have been got from them unless torture was applied.” It was evidently desired to bring Sir Thomas to a traitor’s death at Tyburn by any means.

Cox added that:

‘Sir Thomas was examined under torture, if not on this occasion, at least during the following months which he was to spend in the gloomy dungeons of the Tower. To inflict the extremity of torture on a Catholic was Topcliffe’s highest joy.’

But the attempts to indict Sir Thomas as a traitor failed. Nothing was proved against him except his non-attendance at church..

Camm concluded:

And so the last act of the tragedy begins. We hear the heavy portals of Traitors’ Gate clash behind the brave old knight, and then there is silence. He was now in his 74th year, and he had been thirty years in bonds for Christ. The unbroken solitude and complete isolation of a close prisoner in the Tower made it a very severe punishment even for young and healthy men. It is no wonder that the old knight’s health broke down under the strain, and that he died a ‘natural’ death in less than nine months.

One thing that had never been in question was Sir Thomas’s loyalty to the Crown. As Joseph Tilley wrote:

This gentleman was allowed by his enemies to be of irreproachable character, of a kind heart and munificent disposition; of great scholastic attainments…The temporal powers of Elizabeth had scarcely so loyal a subject…His persecution by the Councils of Elizabeth is piteous.

Richard Topcliffe occupied Padley Manor for a spell of at least six years. Thomas Fitzherbert, nephew and traitor, came into possession of Norbury as life tenant but in1598 complaints against him came before the Privy Council and he sought sanctuary in the city of London. He was still at large in February 1599, and died intestate and childless in 1600. As Bede Camm put it, ‘So no future Fitzherbert was to have the traitor’s blood in his veins.’ After Thomas’s death the properties of Norbury, Hamstall Ridware and Padley, which were all entailed, were ultimately recovered and restored by Thomas the younger’s brother, Anthony Fitzherbert. Shortly after, in 1601, according to Stebbing Shaw, ‘the manor and parks of Hamstall Ridware and Rowley were conveyed to the use of Sir Thomas Leigh, Knt. and dame Katherine his wife, and the heirs of said Thomas Leigh’, of Stoneleigh, Warwickshire.

In 1939 in a newspaper interview, Mary Shelton, née Handy, recalled her time as a servant at Hamstall Hall during the 1850s, when she was a very young girl. She remembered one of the bedroom walls was found to be hollow and the removal of a length of boarding revealed a small apartment in which, to everyone’s amazement, was found a stone image of the devil replete with horns ‘shaving a pig which was covered with red skin’. She said she had been told that the Hall was once a convent (for which there is no evidence) and she presumed that in olden days when a nun transgressed the rules of the Order she was thrust inside the apartment to do penance. This had left me to wonder if this room could have in fact been a 16th century priest hole in which to secrete a Marian priest. However, as the Leigh family had the hall largely rebuilt during the 17th century, even this seems unlikely.

Appendix 1

Collections for a History of Staffordshire, edited by the William Salt Library (Volume VI, New Series, Part 1, 1903).

THE INVENTORY OF CHURCH GOODS AND

ORNAMENTS TAKEN IN STAFFORDSHIRE

IN 6 E. VI (1552).

ARCHDEACONRY OF STAFFORD

Introduction

“Ornaments Rubric,” as found in our Prayer Books, has two distinct subjects – the ornaments of the Church and the ornaments of the minister. The word ornament has come to have a different meaning from that it originally had, as its first idea was “equipment” or “furniture,” especially of a military kind, and so it is easily transferred to something handsome to look at; but in the Ornaments Rubric the word comprises not only that which is decorative and comely, but also that which is necessary. [The Rubric was the set the rules or instructions pertaining to the Ornaments or objects allowed by ecclesiastical law which could be used at morning or evening prayer.] The first Prayer Book was issued in 1549 and the second Prayer Book in 1552; and in that year a commission was issued to take an inventory of all the ornaments then existing in the Church. The commission illustrates first, the lawless spirit of confiscation which was abroad, and secondly what ornaments were in use in the year 1552. In the Record Office, a fairly complete series of the inventories taken in many of the counties exists, and that for Staffordshire is hereby appended, omitting the churches included in the archdeaconry of Stoke, as the inventory of their goods is to be found in the Notes on the Archdeaconry of Stoke-on-Trent, compiled by the Rev. Sanford William Hutchinson. In the Prayer Book of 1549, there is no rubric directly referring to the ornaments of the Church as a whole, and as none of the ornaments previously in use are forbidden by any rubric, the most important may be said to be enjoined, at least if mentioned in the course of the rubrics, as are the altar, chalice, paten, corporas, poor man’s box, font, pulpit and bell. The list is defective, but the Act of Parliament, which enacted the Service Book, did not deal with the ornaments of the Church, for they were dealt with in a series of injunctions issued in the name of the King. By these injunctions all “images, shrines, pictures, paintings, and all monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimage, idolatry, and superstition” were to be destroyed. As contentions then arose, as to what images had been abused, a much more stringent order was issued by the Archbishop in 1548, that “all images should be removed and taken away.” In the Prayer Book of 1552 we find the rubric about the ornaments to stand: “And the chancels shall remain as they have done in times past,” but for the ornaments of the minister one rubric takes the place of the two former ones, and the surplice is ordered to be used alone, which was a concession to the Puritan party. Under the influence of this party the patrons, churchwardens, and sometimes the people themselves seem to have taken advantage of the change of opinion, and peculation [i.e embezzlement], became the order of the day. To meet this, the Crown issued the commission, of which the “Inventories” were the result. For the commissioners were to turn to the use of the Crown the robberies then going on, and in many counties are lists of the actual thefts, which were proved to have taken place. It may be asked why the Crown did not give power to the commissioners to sell these goods and pay the money into the Exchequer? It was probably on the grounds of policy that this was not done, but in January, 1553, a commission was issued to confiscate such Church goods as could be turned into money, when it was ordered that “all ready money, plate, and jewells are to be confiscated to the King’s use, all copes, rich vestments, and bells to be sold, and the profits thereof to be given to the King.” These inventories enable us to form some idea of the beauty and costliness of the ornaments, which the devotion and piety of the parishioners endowed their churches with; but we must remember that they were not confiscated on the ground of any change of ritual, but merely for ‘pecuniar’ [monetary] reasons to benefit the Royal Exchequer. The youthful Sovereign, with a charming simplicity, thus wrote in his private journal: “It was agreed that commissions should go out to take certificate of the superfluous Church plate to mine use, and to see how it had been embezzled.” Froude in his History of England thus describes the work of sacrilege: “In the autumn and winter of 1552-3, no less than four commissions were appointed with this one object [of spoliation], four of whom were to go over the often-trodden ground and glean the last spoils which could be gathered from the churches. In the business of plunder the capacity of the Crown officials had been far distanced hitherto by private peculation. The halls of county houses were hung with altar clothes; tables and beds were quilted with copes; the knights and squires drank their claret out of chalices and watered their horses in marble coffins.”

F. J. Wrottesley.

STAFFORDE.

HUNDREDUM DE OFFELEY.

A juste trew and parfett survey and inventorie of all goodes, plate, juelles, vestements, belles and other ornaments of all churches, chappells, brotherhoddes, gyldes, fraternities and compones within the Hundred of Offeley in the Countie of Stafford taken the seventh day of October in the sixte yere of the Rayne of our Sovereyn Lord Kyng Edward the Syxte by Thomas Gyfford and Thomas Fytzherbert Knyghts and Walter Wrottesley Esquier by virtue of the Kings commission to them directed in that behalf as her after particularly appereth.

PYPE RYDWARE.

Fyrste one challyce the cuppe of gilt sylver and the fote tynnc; ij vestements of satten of burgs; ij albes; iij alter clothes; a cope of dornyxe; a surp’ es; ij towells ;

ij cruetts of leade; ij corporas with their cases; ij lyttyll belles and iij other lesser belles.

RYDWAR MAVESON.

Fyrste ij challeses of sylver parcell gylte; iij copes, one of velvet, one of dornyxe, the thyrd of grene sylke; one crosse of copper and a clothe for the same; vj vestements, one of chamblet, one of dornex; iij of grene sylke, and the syxte of tawney; tooe ornaments of dornex one for subdiacone and one for deacon; iiij albes; viij alter clothes; v towells; iij corporas with cases; one cruett; ij candelstyks of laten; a water stoche of brasse; iij belles, one sancte bell, and ij sacrynge belles.

RYDWARE HAMPSTALL.

Fyrste one challes of sylver with a paten; ij copes, one of blewe damaske and the other of clothe of badeken; vj vestements with all thyngs therto belongynge, one of red satten, one of blewe satten, one of fustyan of naples and the other tooe of clothe of badken; iij corporases; vj alter clothes; iij towells; one crosse of copper and gylte; one surples; ii belles; ij sacrynge belles.

GLOSSARY

Albe. Latin alba, i.e., alba tunica, a vestment of white linen, reaching to the feet, with close-fitting sleeves. It was probably worn in common life by bishops and priests, but afterwards, as custom changed, became an ecclesiastical garment only. At a later date a particular form of ornament was added called “apparels.”

Apparells were pieces of embroidery stitched on to the albe, just over the feet and over each wrist and on to the amice to form a collar.

Baudkyn, baudekin, baudekyn, bawdkin, badken. A rich embroidered stuff, originally made of warp of gold thread and weft of silk made in Bagdad; later, a rich brocade or a rich shot silk.

Bruges or burges. A city in Flanders which gave its name to a particular make of satin.

Chalice, challes, chales. Latin calix-calicem. The cup in which the wine is administered in the celebration of the Eucharist.

Chamblet, chamblot, form of camlet. A beautiful and costly Eastern fabric made of wool and silk.

Cope. A vestment of silk or other material made of a semi-circular piece of cloth worn in processions, at vespers, and on other occasions, as coronations. By canons of 1603 “copes were to be worn in Cathedral Churches by those that administer the Communion.”

Corporas or corporal. Corporal cloth. A cloth, usually of linen, on which the consecrated elements are placed during the celebration and with which they are covered after the celebration. The word was used in the Prayer Book of 1549. A corporal-case is a case for the corporal, now called a burse.

Cruett. A small bottle or container for holding the wine or water in the service of the Eucharist.

Damask, from the city, Damascus. A rich silk fabric woven with elaborate designs and figures.

Dernick or dornyxe, dornex. A species of figured linen named from Doornik or Tournay in Flanders.

Fustyan, fustian. A variety of heavy cloth woven from cotton in Naples.

Latten, lattyn. French, laton, brass. An alloy of copper not distinguishable from brass.

Parcel gilt, i.e., partially gilt.

Paten. Latin patina. A small circular plate used to place the bread on in the service of the Eucharist.

Sacringe bell. Small bell rung at the Elevation of the Host.

Sanctus, sancteor saunce bell. Hung in a campanile over the chancel and rung at the Sanctus.

Stoche. A stone basin inserted in the wall.

Surplice, surplus. i.e., over-pelisse, loose white linen vestment varying from hip-length to calf-length, worn over a cassock by clergy.

Towell. These were houselling cloths used for laying along on the communion rail in front of the communicants, a custom still retained in some Catholic churches and chapels.

Tyncc. Tin.

Vestment or vestement. This was the paenula, planeta, casula, or chasuble used as the chief vestment in the highest office. The paenula was the “cloke” of St. Paul, 2 Timothy. It often included the whole of the prescribed dress of the celebrant ˗ chasuble, amice, stole, maniple, and girdle.

Appendix 2

Recusant Rolls of the Exchequer: 1581 – 1592

Published by the Roman Catholic Society. Volume 71. Extracted by Dom Hugh Bowler; edited by Timothy J. McCann. 1986

Each year, the medieval English Exchequer, the government department concerned with finance, produced a parchment roll known as the Pipe Roll or Great Roll. The rolls contain the yearly accounts of the county sheriffs, recording debts and fines owed to the government, and any payments made during the course of the year. The roll was called the great roll because of its size and significance; it was probably called the pipe roll because, when rolled up, it looked like a pipe.

Initially penalties owing to the crown for recusancy, as for other religious offences, were also recorded on the Pipe Rolls of sheriffs’ accounts amid numerous unrelated items of royal revenue. After 1592 a century-long series of Pipe Rolls specifically concerned with recusants convicted under the 1581 and later Acts were inaugurated. These were known as the Recusant Rolls of the Exchequer (1592-1691).

Some Hamstall Ridware Recusants as Identified in the Pipe Rolls

Alsopp, Isabel, wife of Richard Alsopp of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 8 months recusancy from 1 August 1585: convicted. 13 March 1585/6.

Arnold, Margery, wife of Thomas Arnold, ‘yoman’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs, 8 months recusancy from 1 Aug 1585: convicted. 13 March 1585/86 and a later convicted date of 1 Aug 1586.

Arnold, Richard, (alias) Audley was a young priest, son of one of the tenants of Hamstall Ridware. [Father Martin Audley ‘faiythful body servant of Sir Thomas Fitzherbert’].

Bakewell, Robert, ‘husbandman’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 6 mths recusancy from 6 Sept 1587 – 22 July 1586.

Barlowe, Walter, ‘clericus’ of Rydware Hamstall 4 months recusancy from 31 March 1582 to 2 Aug 1582: convicted. 2 Aug 1582. Debt re-enrolled.

Barlow, Walter, a Marian priest living at Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. in 1582 was probably chaplain to the Fitzherberts: he was in the Marshalsea for some months and then in Stafford Goal in 1586.

Blunte, Isabel, wid of Blithebury (Blithbury), Staffs. ‘supposed recusant and fugitive’. Record of land seizure 4 Sept 1589. Rental of lands seized 4 Sept 1589. The seized lands of Isabel Blunte at Blithbury were discharged in 1591.

Browne, Timothy, ‘laborer’ of Hampstall Ridware, Staffs. 6 months recusancy from 15July 1588: convicted. 14 March 1588/9. Goods value £2.12.10 seized 4 Sept 1589.

Collier, Thomas, ‘clericus’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 8 months recusancy from 1 April 1588: convicted. 21 July 1589.

Footnote.

Collier, Thomas, a pre-Elizabethan or Marian priest was deprived as vicar of Uppingham in Rutland and as a canon of St. Pauls Cathedral. In 1560 he came to Staffordshire and he obtained (? from Richard Fitzherbert) a small farm called Bancroft, presumably in the vicinity of Hartesmere, the Fitzherbert’s residence in Hamstall Ridware, for which he owed a rent of £3.6.8 yearly. He eventually became involved prominently in recusant activity in Staffs., and after having been convicted of recusancy in 1588 became publicly known as a recusant ’fugitive’ for having, with nine other neighbours, gone into hiding when the pursuivants came to investigate his financial status. The man responsible for this investigation was one Edward Thorne, a bitter anti-papist, who had obtained from the Crown on Dec 22 1591 a lease of the lands of Fitzherbert and Collier for £10.6.8 per annum with a further commission to collect, and if necessary, to drive away their cattle, and seize all other possessions, ostensibly for the Queen’s use. A sum of £125.13.8 was collected in this way, and was carefully allotted to the Queen in the records of the exchequer. In the meantime on 9 June 1595 Richard Fitzherbert died, and shortly afterwards the notorious Edward Thorne.

Collyer, Thomas, ‘supposed recusant and fugitive’ of Staffs. Goods valued £4 Sept 1589.

Collier, Collyer, John, ‘husbandman’ of Hampstall Ridware, Staffs. 6 months recusancy from 6 Sept 1587: convicted. 22 July 1588. Goods value £7.1s. Seized 4 Sept 1589.

Cooke, George, ‘husbandman’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 6 months recusancy from 25 March 1588: convicted. 14 March 1588/9. Goods value £5.0.4 seized 4 Sept 1589.

Coxon, Gertrude, ‘spinster’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 4 months recusancy (undated): convicted 21 July 1589.

Coxon, Henry, ‘labourer’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 6 months recusancy from 25 March 1588: convicted 14 March 1588/9.

Fitzherbert, Sir Thomas, Knt of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 12 months recusancy ending 1 April 1587 when convicted. 7 months recusancy from 24 March 1587/8 to 6 October 1588 (Fine £140 paid 2 Dec 1588). Recusancy for one year from 6 October 1588. Annual fine (£260) paid.

Fitzherbert, Richard, ‘gentleman’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. ‘recusant and fugitive’. Goods value £30.5.4 seized 4 Sept 1589. Record of land-seizure 4 Sept 1589, tenement called ‘Hartesmere’ in tenure of Edward Thorne, with lands at Bromley Hurst, Staffs. Rental of seized lands. Seized lands let by Crown to Edward Thorne from 22 Dec 1591.

Footnote

From the Privy Council papers it can be seen that Thorne was no stranger to the Fitzherbert family. He had already dispossessed Richard Fitzherbert of the estates of Hartsmere and Bancroft, in spite of Sir Thomas’ protests. ‘He had carried off all his cattle, and was in fact a veritable pest to all the faithful in Staffordshire’.

Heveningham, Ann, wife of Walter Heveringham Esq. of Pipe Ridware, Staffs. 6 months recusancy from 6 Sept 1587: convicted 22 July 1588. [Ann was the niece of Sir Thomas Fitzherbert].

Knowles, William, ‘yoman’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 8 months recusancy from 1 Aug 1585: convicted. 13 March 1585/6.

Knowles, William, ‘husbandman’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 12 months recusancy from 6 Sept 1586: convicted. 25 March 1588.

Knowles, Agnes, his wife (same parish, recusancy period and conviction date). An older conviction date of 1 Aug 1586.

Knowles, Knolles, Agnes, ‘widow of [Hamstall] Ridware Staffs, 4 months recusancy from 13 March 1585/6: convicted 4 Sept 1589. Goods value £11.1s. Seized lands let by Crown to Edward Thorne from 22 Dec 1591.

Knolles, Agnes, ‘widow of Sandbarrow’ one of the original ‘fugitives.’

Needham, Nedeham, Nedham, Brian, ‘clericus’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 4 months recusancy from 31 March 1582: convicted. 2 Aug 1582.

Poker, William, ‘supposed recusant and fugitive’ of Staffs – Goods value, £22 – 10s, seized 4Sept 1589 – x (14)

Tonge, Agnes, wife of William Tonge, ‘yoman’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 8 months recusancy from 1 Aug 1585: convicted.13 March 1586/87.

Wade, Margery of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. ‘A tenant or servant of Sir Thomas Fitzherbert’ was listed as a recusant in 1577.

Ward, Thomas, ‘laborer’ of Hamstall Ridware, Staffs. 6 months recusancy from 6 Sept 1587: convicted. 22 July 1588

Diocesan Returns of Recusants for England and Wales 1577 [Including some names not previously mentioned]

‘The names of all such persons, gentilmen and others, within the countye of Stafford which come not to the churche, to hear divine service’.

Hamstall Ridware parishe

Sir Thomas Fitzherbert Knight

Richard Fitzherbert esquire and Marye his wife

William Bridgeman and Mawde his wife

Richard Twyford and Elizabeth his wife

Margarett Collier

Roger Gretton and Alice his wife

Alyce Baylye, Anne Baylye

Mawde Knolles

Katheryn Bankes,

Cicelye Maskerye,

Elizabeth Cooke

Richard Alsoppe

William Abell

John Typper

John Bridgeman

Thomas Coxon

Thomas Arnold

William Poker, husbandman

Matilda Poker of Hampstall Ridware owes £80 for the like, wife of William Poker.

Margaret Eke of Hampstall Ridware, widow.

Katherine Eke of Hampstall Ridware, “spinster”.

Margery [or Margarett] Arnold, wife of Thomas Arnold of Hampstall Ridware, “yoman”.

Eleanor Burges of Hampstall Ridware, “spinster”

Sources

Articles by Nicholas Fitzherbert 1985 at Catholic Herald. Accessed 9 January 2021

Camm, Dom Bede. Forgotten Shrines: An Account of Some Old Catholic Halls and Families in England and of Relics and Memorials of the English Martyrs. (1910).

https://books.google.co.uk Accessed 17 January 2021

Collections for a History of Staffordshire: Volume VI. New Series. Part 1. (1903). Edited by the William Salt Library. https://www.staffordshirecountystudies.uk Accessed 8 April 2021

Cox, Dr J. Charles. Vol III Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire (1877). https://books.google.co.uk Accessed 15 February 2021

Cox, Dr J. Charles. Vol VII of the Derbyshire Archaeological Journal (1885).

Norbury Manor House and the Troubles of the Fitzherberts

https://books.google.co.uk Accessed 15 February 2021

Cox, Dr J Charles. Three Centuries of Derbyshire Annals. (1890) Accessed 12 May 2022

Dargue, William. Park Hall Part Two – Troubled Times. https://birminghamhistory.net Accessed 12 February 2021

Green, Nina. 2014. Transcript of Sir Anthony Fitzherbert’s will. The National Archives. PROB 11/127/312.

https://www.oxford.shakespeare.com Accessed 21 March 2021

Greenslade, Michael W. Catholics in Staffordshire 1500-1850 (2006).

Hackwood, Frederick William, writing the ‘Chronicles of Cannock Chase’ in the Lichfield Mercury of 1903. https://www.findmypast.co.uk British Newspaper Archive. Accessed 5 April 2021

Morris, John. The Catholics of York under Elizabeth (1891). https://www.ebooksread.com Accessed 4 February 2021

Shaw, William Arthur. Knights of England (1906). https://www.archive.org Accessed 8 April 2021

Stebbing Shaw. The History and Antiquities of Staffordshire (1798 – 1801).

Talbot Papers / The National Archives. https://discovery.national.archives.gov.uk Accessed 9 January 2021

The Exchequer Pipe Rolls 1581-1592. https://issuu.com

Published by the Roman Catholic Society. Extracted by Dom Hugh Bowler. Edited by Timothy J. McCann (1986). Accessed 10 February 2021

The History of Parliament: The House of Commons

https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org Accessed 27 February 2021

Tilley, Joseph. Old Halls, Manors and Families of Derbyshire (1893). Transcriptions by Rosemary Lockie https://www.books.google.co.uk Accessed 17 January 2021

Verner, Laura Anne. Post Reformation Catholicism in the Midlands of England (2016). https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal Accessed 7 Feb 2021

Derbyshire Miscellany. No 17. Spring 2004. The Fitzherbert

Family – Derbyshire Recusants. John March. https://www.derbyshire.org.uk Accessed 14 May 2022

Author: Helen Sharp