From the Chair

This is my first report since being appointed Chairman in October 2023. Having recently attended the final presentation evening of our winter season, it’s nice to look back and reflect on a collection of talks which were very well received by all those who attended.

I’m sure we all learned a great deal as well as being entertained. I’d like to thank Helen Sharp for her efforts in researching and making all the arrangements to bring the speakers to our meetings.

It has been gratifying to see the meetings in the hall so very well attended, including a good number of visitors. Some of those visitors also decided to become Society members, and they are most welcome. On the subject of new people, we are always keen to welcome members onto our organising committee. Our meetings are also a nice social occasion and if anyone is interested in joining us, please contact myself or any committee member.

I will conclude by mentioning the summer visits. Helen is about to announce the arrangements she has made, so keep a look out for the details.

She is also working on the next series of talks for the coming winter, and we’re all looking forward to that.

Have a good summer and I hope to see you all in a few months.

Roy Fallows

Sir Robert Peel

A talk by Roger Field on 2 October 2023

This was the first talk of the winter programme. It followed the Annual General Meeting where reports were presented by committee officers and new officers were elected.

Mr Roger Field from the Peel Society, based at Middleton Hall near Tamworth, gave an interesting talk on Sir Robert Peel and the origins of the police service in this country. The Society was set up to honour one of the area’s most famous people, as the local council didn’t seem too interested in making more of the man and the history.

Robert Peel was born in Chamber Hall, Bury, Lancashire in 1788. His father was the industrialist and parliamentarian Sir Robert Peel, 1st Baronet. Sir Robert Snr was one of the richest textile manufacturers of the early industrial revolution. Robert Peel’s grandfather, known as ‘Parsley’ Peel, developed a means of printing on calico without the colour running when washed. The family came from a long line of Lancashire farming yeomen.

The family eventually moved to Drayton Manor, near Tamworth. The hall was demolished some years ago and the grounds are now the Drayton Manor theme park. Only a tower remains from the original hall.

Robert Peel was educated in Bury, Harrow and Oxford University where he gained double firsts in Classics and Mathematics. He was the first Oxford student to achieve that feat.

Peel entered politics in 1809 at the tender age of 21. He became MP for one of the ‘rotten’ boroughs, Cashel in Tipperary, Ireland. His sponsors were his father and Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington. The seat, which only had 24 voters, was effectively bought for him. In 1812 Peel was appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland. This was a time of turmoil in Ireland, mainly due to Catholic majorities being discriminated against. Legislation was enacted to allow more magistrates to be appointed to troublesome areas and also have paid special constables. These were the first ‘peelers’.

Peel was a rising star in politics and in 1822 the Tory government appointed him Home Secretary. He set about reforming criminal legislation and reduced the number of crimes punishable by death.

The Irish ‘problems’ continued to cause rumblings in Parliament until an Irish emancipation act settled things somewhat. Robert Peel was eventually elected MP for Tamworth in 1830 and remained so until his death.

During the early 1800s London was regarded as a dangerous place. Good citizens were afraid to visit certain areas, particularly after dark. Local parishes appointed watchmen to help the situation but they were next to useless. They were called ‘Charlies’ after King Charles II who started the system. They were paid two shillings a night. Because they were so ineffective they gave rise to the phrase ‘Right Charlie’ or ‘Proper Charlie’. The other well-known law enforcers, the ‘Bow Street Runners’, were never like a police force. There were only eight of them and they didn’t wear a uniform. They acted to enforce actions on behalf of magistrates at Bow Street Court. There were Bow Street patrols who were called Redbreasts in recognition of the red waistcoats they wore. Peel had tried to start a police force in 1822, but it failed because there was a fear that such a body would interfere with liberty. One of the reasons for wanting a police force was the Peterloo massacre in 1819 when military units killed several protestors near Manchester. In 1829 Robert Peel promoted an Act authorising the formation of a paid police force in London. This was after Peel had seen how effective the constables were when he was in Ireland. Peel stipulated that those appointed were to have no military connections. There were to be no ‘back door’ appointments of ex-army officers. 895 constables were appointed, plus supervising officers. They were paid a guinea a week and worked 12 hour shifts for six days a week. They were allowed one week unpaid leave.

One of the problems with the police and many others at that time was drink. Water was not safe so beer was drunk by everyone, sometimes to excess. Police Constable No.1 only lasted for four hours. He was found drunk and dismissed. Half of the police force was sacked in the first two years for drunkenness.

In 1839 the County Police Act was passed to allow counties to set up their own police forces. Many autonomous boroughs did the same.

During the First World War, due to men serving in the military, females were appointed to the post of constable, although they had no power of arrest until 1923. It is reported that when the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police agreed to allow woman into the force, but he didn’t want ‘vinegary spinsters or blighted middle-aged spinsters’, and if they got married, they had to leave. The women had to put up with a lot. This was illustrated in the 1930s when the Commissioner placed an advertisement in a newspaper offering applications to join the police. They should be ‘good looking but hefty and able to put up with a rough and tumble’.

Policing continued in the traditional way for most of the 20th century until, in 1967, the ‘Panda’ system was adopted by most forces. This was regarded by many as putting the police out of touch with the general public.

Roger included in his talk a couple of ‘war stories’ from his time with Birmingham police involving the value of informants and his role in the city vice squad.

This was an interesting talk, well received by a good attendance.

Roy Fallows

Training Accidents and Losses at RAF Lichfield between 1941 and 1945

A talk by Lyn Tyler on 6 November 2023

Lyn Tyler and Richard Green from Fradley Heritage Group visited on 6 November to explain the importance of Fradley Aerodrome, or more correctly, RAF Lichfield, during the Second World War.

With rumblings of the advent of war becoming more insistent, the construction of an airbase at Fradley began in 1938, becoming operational in 1939. It began life as a maintenance unit, receiving new aircraft from factories to make any necessary modifications and it repaired craft that were damaged in service. Once airworthy they had to be delivered to their appropriate squadron or other destination. These deliveries were initially done by men, but it soon became apparent that more personnel were needed to deliver the aircraft and the newly created Women’s Auxiliary Air Force was drafted in. These were missions fraught with danger.

In 1941 the airfield became dual purpose. Whilst maintenance and delivery continued, RAF Lichfield became Operational Training Unit (OTU) 27. Its primary role was to form and train aircrew for front-line bombing operations using Wellington Bombers. The men were from all parts of the Commonwealth, but the largest contingent came from Australia.

The service population rapidly expanded to 3,500. The men were housed, for the main part, in barracks on site, but a number of more permanent staff were billeted with local residents. An amusing anecdote concerned a nine-year-old boy, Colin. One can just imagine the excitement that the airfield activity created, real-life Biggles stuff! Well, Colin would go to bed each night and pray, ‘Dear God, please let us have a pilot’. This was not to be, they only ever had maintenance crew!

The training was incredibly intensive. There were usually six men in a crew, so the first thing they had to learn was to be a cohesive team; after all, they would need to be able to depend on each other. Surprisingly, they chose their own crews. The new recruits were corralled together in a hangar and left to ‘sort themselves out’. Even though some of the men may have had some basic flying experience, it probably wasn’t much. All aspects of being a member of this crew had to be taught. They had to learn taking off and landing, map reading and navigation, wireless operation, night, all weather and all terrain flying and bombing practise.

Sadly, a combination of factors led to numerous training accidents. Causes included poor weather conditions and mechanical failure. Many of the Wellington Bombers used at Lichfield were old and prone to mechanical failure. Engine failure was common, but failure of wireless equipment was also a serious problem, especially during night flying exercises. Aircrew error was probably the most common cause of accidents, but this implies no criticism of aircrews. They were young and inexperienced. Some pilots, for example, didn’t even hold a driving license, but found themselves at the controls of a Wellington Bomber. In some cases, obstructions such as trees and buildings and even flocks of birds caused accidents. And, of course, sometimes enemy action brought down aircraft, as aircrew nearing the end of their training were sometimes deployed because of a shortage of experienced crew.

The Churchyard of St Stephen’s at Fradley stands testament to many of those who lost their lives in the course of their training. There is a section where there are 34 Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones for these airmen, the youngest of whom was only 17, but this is only a fraction of fatalities. Some of those who died were repatriated to their country of origin and others were not recovered or could not be identified.

The following is a breakdown of all training accidents at 27 OTU Lichfield

- 1941 – 9 training accidents – 6 killed – 11 injured

- 1942 – 16 training accidents – 48 killed – 32 injured

- 1943 – 28 training accidents – 67 killed – 21 injured

- 1944 – 19 training accidents – 33 killed – 13 injured

- 1945 – 3 training accidents – 0 killed – 0 injured

In 1941 there was one other training accident which involved a civilian, an Armitage man, Arthur Salt, who had fought in and survived the First World War, employed as a tractor driver at the airfield. He was standing by his tractor when an aircraft was preparing for take-off. Its wing clipped the tractor which tipped right over onto him and he died from his injuries. He is buried in St John’s Churchyard. Armitage. There is also a road named after him in Fradley – Salt Way.

Another village boy also had quite the adventure. It seems that locals freely wandered round the site, even nine-year-old boys! One day he went missing, but in those days, children had freer rein than now, so it was much later in the day when his family began to be concerned. However, he turned up unscathed and explained that he had had a ride in a Wellington Bomber! Health and Safety – it wouldn’t happen today.

Word of a ‘prang’ would soon get round the boys of the village, who would set off in search of souvenirs from the wreckage. Oh! the innocence of youth.

Helen Sharp

Here we are again: a (very) brief history of pantomime

A talk by Dr Ann Featherstone on 4 December 2023

Ann Featherstone is a retired lecturer in theatre history and has acted extensively throughout her life, which made this talk a really lively, enjoyable and informative one. She began by saying that at one time every town would have a pantomime and this would often be a child’s first experience of the theatre. Perhaps children are the audience most willing to suspend their disbelief – a necessity for appreciating panto.

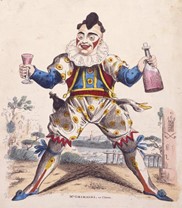

Pantos originated as short afterpieces – perhaps 20 minutes – to a theatrical evening, featuring knockabout humour. Normally they told a well-known fairytale, followed by a section called the Harlequinade in which characters from the commedia dell’arte tradition performed. The comedy was physical, rude, slapstick. I did not know that the latter term originated with an object – two pieces of wood which clapped together – used by actors to whack each other and to emphasise the comedy.

In 18th century London John Rich promoted panto at his Lincoln’s Inn Theatre, playing Harlequin. His productions used dance and mime with no dialogue at all, and they became real extravaganzas. Artists were hired to build complex and realistic scenery, which may have taken as long as 30 minutes to change between scenes. The aptly named Rich became rich through the success of his productions and built the Covent Garden Theatre. His great rival was David Garrick at Drury Lane, who introduced dialogue and satirical material – for example, about contemporary politics.

Garrick hired Giuseppe Grimaldi, whose son Joseph (1779 – 1837) became the greatest pantomime artist of all time. He transformed the character of the Clown, making him a wild and anarchic creature, with grotesque make-up and huge pockets full of strange objects (an endless chain of sausages, for example). He is the forerunner of the modern pantomime Dame.

Garrick hired Giuseppe Grimaldi, whose son Joseph (1779 – 1837) became the greatest pantomime artist of all time. He transformed the character of the Clown, making him a wild and anarchic creature, with grotesque make-up and huge pockets full of strange objects (an endless chain of sausages, for example). He is the forerunner of the modern pantomime Dame.

In Victorian times, panto became a performance for children. In addition to spectacular scenery, there were extravagant and expensive costumes. There were often throngs of extras, often using local children as choruses or dancers, and this tradition continues with children from local dancing schools in modern panto.

By the late 19th century, panto was being influenced by music hall, which had a tradition of audience participation and that became part of the panto tradition (‘It’s behind you!’). Celebrities from music hall brought audiences to the panto; stars like Dan Leno created the pantomime Dame. There is no attempt to disguise the masculinity of the actor, which is the source of the humour. Other traditions developed: for example, the Principal Boy is always a young woman.

Panto was kept going in British theatres through both World Wars, often using women or ageing actors. It was also taken overseas to entertain the troops, and British PoWs staged pantos in their camps. Postwar panto has been infiltrated first by radio and then by television stars and it is often more like a variety show than a coherent theatrical performance.

The tradition of pantomime is largely incomprehensible to many nationalities, especially Americans. Having taken my American sister to her first panto and having watched her total astonishment and incomprehension at the entry of three Ugly Sisters turn to helpless laughter, I can certainly second that.

This was a very entertaining talk, which was a perfect kick-off to the Christmas season.

Marty Smith

50 Years on the Roof: One Man’s Thatching History

A talk by David Wood on 8 January 2024

Dave Wood may have been seen recently re-thatching a house in Rugeley Road, Armitage. It was last re-thatched in 1963, which gives an indication of the longevity of a properly thatched roof. It is possible that during his 53 years as a thatcher he has worked on every thatched house in the area.

Dave Wood was a nosy child. He grew up in Derbyshire and was fascinated by the contents of a neighbour’s truck. The neighbour was called George Mellor and he was a thatcher. What fascinated Dave was all the materials George carried and he wanted to know what it was all about. George invited Dave to join him at the weekends (he had spoken to Dave’s parents and had their permission), when he gradually learned the art of thatching. He regularly accompanied George at the weekends and during the school holidays. At the age of 13, Dave spent more time with George than at school. It was probably inevitable that Dave became an apprentice thatcher with George when he left school.

His training was in Derbyshire, Staffordshire, and the surrounding counties. At first, he watched and learned. Then he carried out small repair jobs and worked up to thatching roofs – but only the side that could not be seen by the public! The reason for this limitation was because George’s reputation relied on what could be seen. But eventually, George decided he was ready to go solo on a job at a property at Melbourne in Derbyshire. He was observed by another thatcher who passed Dave as a qualified thatcher. In time, Dave became a member of the National Society of Master Thatchers.

The traditional material for thatching roofs was straw. However, to increase the grain yield, the plants are bred to have short stalks and the resultant straw is unsuitable for thatching. The advantage of straw is that it can be tied into bundles and will compress and not crack. The bundles are bound by twine impregnated with tar. Each bundle is about 20cm thick. The bundle is tied to the roof rafters. When layered up, these form a waterproof layer. Before twine was used, the bundles were tied with briers.

Now that straw is not available, the material used is Norfolk reed. The traditional reed beds are poorly managed and quality material is imported from Hungary. Unlike straw, reeds cannot be compressed without cracking, so must be loosely bound and instead of being tied to the roof rafters, they are pinned in place with iron staples.

Some customers like to have a bird or an animal on top of their completed roof. Dave does not make them himself but buys them in.

As well as house roofs, there is a market for thatch covered bird houses, bird feeders and dog kennels.

David Smith

L FOR LEATHER

The History of Jabez Cliff & Co. 1793-2013

A talk by Cliff Kirby-Tibbits on 5 February 2024

Cliff began by passing round some examples of the company’s leather products: collar breasts, saddles, bridles and a gold belt used for the drum horse in military parades. He then took us on a journey through the company history, which, though firmly based in Walsall, took us as far as revolutionary Russia and rambled back and forth through 200 years.

William Cliff, the first of eight or nine generations involved with the leather trade, actually started in the shoe industry in Stafford, before moving with wife Susanna to Walsall, where he made leather breeches. His grandson was a bridle preparer and bridles became the main product in the 19th century. The firm’s premises were long and narrow to minimise rates, which were calculated on the width of frontages, and the atmosphere was smoky and unhealthy.

In the 18th century, Walsall was bigger than Birmingham. But Cliff repeatedly said it was ‘blinkered’, as the town powers refused the canal and the railway, and this hampered its development.

On the death of James Cliff, his daughter and her boyfriend, Fred Tibbits, took over. They were ‘made of strong stuff’ and, with the help of the newly-invented sewing machine, they diversified, making all sorts of leather goods; e.g. golf bags and footballs, and built up the company to the level of 20,000 orders a month. Until 1970, Cliff’s were the world’s leading manufacturers of footballs. Another innovation was the production of matching sets of luggage, which they promoted successfully in large London stores. By 1902, they were making torpedo cases for the Royal Navy.

Probably the most significant advance, however, was in 1904, when Cliff’s took over the failing Barnsby saddlery company, thus becoming a leading name in Walsall’s most iconic product.

At the time of the First World War, when 85% of British leather products were made in Walsall, the manufacturers managed to work together for its duration, but reverted, at its close, to being ‘blinkered’ again.

The speaker’s grandfather was now in charge. He opened up a trade with Russia, which led to an exciting tale of escaping the Communist Revolution. He also managed to keep all his staff on during the General Strike, turned torpedo cases into walking sticks, was knighted, and became Mayor of Walsall.

More recent highlights included a contract to supply the MoD with pack saddlery for the Falklands War, work on Queen Anne’s coach for the Royal Family, and a gift of horseshoes from Queen Elizabeth to President Bush.

Sadly, Jabez Cliff closed down in 2013 and, later, an intruder caused a fire which destroyed its premises.

Phil White

Links with the Leighs – a Tale of Two Counties

A talk by Sheila Woolf on 4 March 2024

This is a tale of two counties, Warwickshire and Staffordshire, and the Leigh family.

Prior to the dissolution of the monasteries Stoneleigh Abbey was occupied by a Cistercian order of monks. They had originally moved from Staffordshire to Stoneleigh; an early link between the two counties.

In 1561 Sir Thomas Leigh, Lord Mayor of London in 1558, bought the Stoneleigh estate and a mansion was built on the site of the former monastic buildings. Leigh’s family and descendants remained at Stoneleigh Abbey until 1993. Sir Thomas established a portfolio of properties across England including Adlestrop and Longborough in Gloucestershire, Stoneleigh in Warwickshire and Hamstall Ridware in Staffordshire.

In 1601 the ownership of Hamstall passed to his son, Sir Thomas Leigh, later made 1st baronet, and for a while the Hall there was his principal residence. This seemed a surprise as it is so far distant from Stoneleigh. Was it because of links the family had with counties further north? Sir Thomas Leigh died in 1626, having married Lady Katherine Spencer, but his son John had predeceased him; his grandson Thomas inherited the estates. He was created the first Baron Leigh in 1643 after his support for the Royalist cause in the Civil War.

The link with Hamstall continued, as Sheila noted his marriage to Jane Fitzmaurice at the church of St Michael and All Angels there in 1642 and his son Thomas, who was to become the 2nd Lord Leigh, was baptised there; brothers Charles and Christopher were also baptised there.

Sheila and Helen Sharp connected with each other during lockdown, and Sheila visited Hamstall Ridware in 2022. Interesting connections between Stoneleigh, Ashow (a village near Stoneleigh) and Hamstall gradually unfolded. In Hamstall church she discovered that the Reverend Thomas Allestree, rector of Hamstall from 1695 to 1715, had previously been rector at Ashow from 1663 to 1676. His sermon ‘A Funeral Handkerchief’ had been dedicated to Lord Leigh and included an obsequious preface thanking him for granting a parsonage in Ashow. Later, in Ashow church she found a list of names of people who held office there and who later appeared at Hamstall. Sheila eventually found a wealth of information showing how the Leigh family bestowed ‘gifts’ of rector posts at Hamstall throughout the following centuries.

Following the death of Edward Leigh, 5th Baron in 1786, the Warwickshire estates were to pass to the Gloucestershire Leighs of Adlestrop. His sister, the Honourable Mary Leigh, was given a life interest first, and on her death in 1806 the Warwickshire lands were transferred to the heir, the Reverend Thomas Leigh, Rector of Adlestrop. Childless himself, on his death the heir was to be his nephew James Henry Leigh.

The link with Stoneleigh Abbey and Jane Austen begins here, The Reverend Leigh suggested that the women of the Austen family, impoverished after the death of the Reverend George Austen, should accompany him on a visit to Stoneleigh. Jane Austen’s mother had been Cassandra Leigh before her marriage, and was first cousin to the Gloucestershire Leighs. She married the Reverend George Austen in Bath in 1764. They had eight children, and Jane was the second youngest. Following the death of George Austen in 1805, the two girls and their mother became essentially homeless, and the Reverend Thomas Leigh invited them to stay with him in Adlestrop and then to visit Stoneleigh. The Austen ladies appear to have enjoyed their time in Warwickshire and it’s believed that Stoneleigh Abbey is the inspiration for Sotherton Court in Mansfield Park. In that novel Jane describes a house and its landscape as being designed by Humphrey Repton. Repton designed the landscape at Stoneleigh in 1809.

Jane Austen, her mother and sisters then went on, later in August 1806, to stay at Hamstall Ridware for five weeks. The Reverend Edward Cooper, Jane’s cousin, had been given the living by the Honourable Mary Leigh and was rector there from 1799 to 1833.

As the 19th century progressed, the links between the Leighs and Hamstall continued.

Chandos Leigh, who became 1st Baron Leigh after the baronry was revived in 1839 (the ‘Second Creation’), married Margaret Willes. Her younger brother Edward became rector of Hamstall, and later Chandos’ son-in-law, Henry Pitt Cholmondeley, took over from Edward as rector…keeping it in the family.

The links go on: Cordelia Leigh, youngest daughter of William Henry, 2nd Lord Leigh of the Second Creation, had a good friend called Alice Skipwith. Her father, Humberstone Skipworth, after holding a number of posts, finally ended up too at Hamstall Ridware as rector! Sheila noted beautiful stained glass there in memory of his first wife.

The remaining link to note is that of the Reverend Coussmaker. He was vicar of Westwood Heath Church–a satellite of Stoneleigh – and then rector at Hamstall Ridware. There he was well-known for his studies into the area’s history; stained glass also commemorates him and his daughter at Hamstall.

When the Leighs no longer wished to live at the Hall in Hamstall, it was rented out to tenant farmers and in the 1920s the estate was sold. One tenant farmer, William Jaggard, discovered the 14th Century chalice and paten, and Lord Leigh had them preserved. The Jaggard family had originated in Leek Wootton, a village a few miles from Stoneleigh. In addition, Sheila had discovered on her 2022 visit to Hamstall a drawing of an object she knew well, which was held at Stoneleigh! It was a medieval scold’s bridle, traditionally described by the abbey guides as ‘certainly not a Warwickshire object’, but in fact, one from Hamstall Ridware.

Paul Carter (based on notes provided by the speaker)

A Date for Your Diary

We will be holding an Open Afternoon in Mavesyn Ridware Village Hall on Saturday 14 September between 2pm and 4pm.

Further details will be in the Autumn/ Winter Newsletter We will be displaying some of the photographs and documents that have accumulated from research projects undertaken by members of the group, including the history of the school, the local pubs, some local families, notable buildings and the pottery at Armitage to name but a few.

THE SITUATION IS DESPERATE!

If you enjoy being part of this society, PLEASE consider becoming a member of the committee. Our number has steadily decreased and two more vacancies are imminent. This means that some of us are having to take on more than one role. Without more help there is a serious danger of the society having to fold. Initially we need someone who may have a fresh outlook on how we do things leading to their taking on a role of responsibility. We usually meet three or four times a year and enjoy a chat and some refreshments as well as a bit of business.

We would like to thank those of you who have been able and willing to help putting away the tables and chairs after meetings – we understand that not everyone maybe in a position to do so!

If however, you feel you could help with serving the teas/coffees before or with the washing up after meetings, that would be very much appreciated.