The following account was written by her in December 2001 in her 82nd year, using information told to her by her grandmother, mother and father.

In 1862 a man by the name of Aaron Bevins gave to his son Jacob 60 guineas to purchase an old cottage and piece of land. It was the first on the left from the Bull & Spectacles (then called the Bull’s Head), down Rugeley Road.

Jacob and his wife, Eliza, took up residence immediately. Realising they would have a family, Jacob started to build a house – which has been enlarged over the years. He only had a small horse and trap and each morning he went to a brickyard in Rugeley to get bricks for his home – whilst he laid them in the afternoon, Eliza went for another load. By working in this way their home was soon complete. In 1865 my grandmother was born – the first of five daughters – who all lived into their late 80s or early 90s before passing away. This first child was Mary Bevins, also known as Polly. The only education she received was in her mother’s kitchen or in a private room at Manor Farm, which used to cost two pence per week if she attended all week, but only a penny if she attended two days. She attended as often as work at home allowed as she wanted to be able to read, write and count. These abilities certainly stood her in good stead in later life. At the age of 13 she had to go out to work to help keep her sisters. Jacob Bevins was a man with great initiative (told to me by Joseph Hammond of Longacre Farm, Blithbury) as he was always needed by farmers in the area.

Jacob decided to use these abilities and then rebuilt the farm house of Mr William Gildart – the first on the left down Hill Ridware Road.

Employment was found for Mary by some devious means at Thorpe Constantine Hall near Tamworth, the home of the Inge-Ing-Lillingstone family, as assistant cook. Her wages were £47 per annum plus her keep and her uniform. She was only allowed one day off per month. On this day she started walking at 5 a.m. and her father started from Blithbury at the same time in the horse and trap to meet her. My grandmother told me they invariably met in the same spot in Coton-in-the-Elms. She had to be back in the Hall by 8.30 p.m. She was so worried about losing her job, her father started to take her back 4.30 p.m., making sure he had plenty of candles to light the necessary coach lamps. Time at home was short but necessary for her to leave her contribution to the upkeep of her sisters.

At this time house parties were the thing amongst the county set – the Earl and Countess of Bradford were often visitors. On one of these occasions the Countess offered my grandmother a better job, which she accepted: £120 per year, plus uniform and keep at Weston Hall, Weston-under-Lizard. She progressed very quickly in such amiable surroundings to head cook. This new status allowed her one day off per week. From Weston Hall it was much easier for her to get home on the mail coach to Rugeley and walk to Blithbury from there. Providing she walked down to Rugeley for 4 a.m. the next morning she got a lift on the returning mail coach in time to supervise the breakfast for the Earl and Countess.

At this time there was a family by the name of Onion employed at Weston Park. They lived in the first lodge on the A5 going towards Weston Park. They had two sons, Frank and George, who the Earl intended for future workmen and so they were sent to a forge at Brewood to train as wheelwrights and farriers. On completion of their training, Frank had eyes for Mary and asked the Earl for a cottage on the estate. He allowed them a cottage at Blymhill and so they married in 1890.

In 1892 a son – Oliver – was born. At this time Jacob had other ideas about getting his eldest daughter nearer home. So, he bought a plot of land on the corner of Hamstall Ridware Road, opposite the Bull & Specs and he proceeded to build a forge and outbuildings so that his son-in-law could earn a living. Frank and Mary moved to live with my great-grandparents. Business was very good and so Jacob built the house that still stands. This property was the first in the area to be built with stone sills and lintels. This was considered a great innovation and people for miles around came to view it. Although my grandparents were installed in the house – my mother was born there in 1894 – they still had no water. A water diviner was brought in from Walsall – he located the supply and so the well was dug for them by local helpers. I believe it was the shallowest well in the neighbourhood. They found water at 40 feet. Business boomed and two more infants were added to the family.

Sad to say, the supply of ale was too convenient and the forge became a drinking den for men for miles around. The Bull & Specs was kept by a smart gentleman – Mr John Tenney. I can remember him always dressed in Harris Tweed suits and he had a goatee beard. My grandmother always said it was the coldest cellar on earth to keep beer. My grandfather had the remedy though. He had a supply of gallon stone bottles and it used to cost four old pence to fill up one with what my grandmother insisted was unsaleable, until my grandfather had improved it with a large dose of ginger and two large spoonsful of sugar – a supply of which he kept in the forge. The bottle was then stood in the warm ashes from the forge to warm up to a palatable drinking temperature. So, a continuous supply was maintained for an ever-increasing number of men who found a horse from somewhere for shoeing. Grandmother could remember as many as 14 horses being tied to the railings awaiting their turn for new shoes.

This drinking den did not conform to my grandmother’s way of family life. It was about 1910 when a crowd of these men were encouraged by grandfather to enhance the Bull’s Head on the pub sign with a pair of spectacles painted with Stockholm tar – a supply of which was kept warm in the forge to paint on any mis-placed nail hole in the horse’s hoof to prevent infection. This is the true story of how it became to be the Bull & Specs no matter what other historians say. This act caused great uproar in the village.

A regular visitor to the forge was Mr Kane from Abbots Bromley who used to ride over on his penny farthing bicycle.

In the late 19th century the gold rush had begun in Canada, and so Mr Kane, together with my grandfather, to avoid any more family confrontation, decided to leave the country in about 1910. They also took Oliver, who was barely 18. They made their way to Liverpool and then worked their way to Canada on a cargo boat. Then they worked on the Canadian Pacific Railroad as stokers to get to Winnipeg, where they abandoned the train to pan for gold. Perhaps the panning for gold was not as good as anticipated, and my grandfather and Mr Kane started a distribution company – a highly successful business – which was still in operation at the time of grandfather’s death in 1931. All of these facts never came to light until 1918 when Oliver called to see the family from France.

The Great War started in 1914 and my grandmother had never heard any word of them. To her astonishment a picture appeared in the daily paper of my grandfather shoeing horses at the front in France with Oliver helping. The caption stated that they were part of the Canadian Yeomanry. My grandmother took steps to obtain an allowance from the Canadian government as she had had such a struggle to keep the home going. She got her allowance, which was paid until her death at the age of 85 years.

Although the war ended in 1918, my grandfather never broke his journey to visit his family as they passed through London. However, my uncle Oliver did. Life at Blithbury was not for him and he yearned to return to Canada, which he did by working his passage back. On his return to Winnipeg, times were difficult and so he joined the Canadian Prison Service. When he retired as a governor in 1968, his one desire was to visit England, which he did, staying with my husband and me at Walton-on-Trent. I chauffeured him around the area to renew many acquaintances from his school days. Unfortunately, he passed away the following year on his way home from the golf club.

It became increasingly difficult for my grandmother to maintain the forge and house, so she decided to sell in 1914. It was bought by the Charles brothers who farmed at Blithbury Bank Farm. They took up residence with their housekeeper, Miss Nellie Shenton – who some years later bought the property from them before building the detached house which still stands at the bottom of the orchard. Meanwhile my grandmother bought Spring Cottage along the Uttoxeter Road, where she lived with my uncle and aunt for many years until they moved to Rugeley, for convenience.

Three of the Onion family had been born at the forge. At this time the large building on the right hand side of the Rugeley Road was a milk factory – owned by the Edwards. Farmers had to take their milk there in tall 17-gallon milk churns very early in the morning. Any milk they did not wish to process was then transported in open wagons to Rugeley Trent Valley station for despatch by rail to other cities.

There used to be a pond on the opposite side of the road. At the deepest end of the pond there was an overhanging platform where often several churns would be standing in the pond to keep cool. Even I can remember seeing these and I was not born until 1920. I believe this factory was closed down when Wilts United Dairies took over the operation at Bromley Hayes near Kings Bromley.

My mother, as a child, remembered seeing several tramps waiting very early in the morning at these large factory doors for the workers to start work and for a drink of whey to slake their thirst on their walk from the workhouse in Lichfield. These tramps then walked on to Uttoxeter workhouse or Stretch’s brewery – both of which were near Uttoxeter station. The brewery was owned by my father’s aunt, a Mrs Fisher, who lived in the large house opposite the entrance to Uttoxeter racecourse. I have been there many times with my father. She was a great and benevolent lady who insisted on these tramps being called night walkers. She allowed them to have a supply of any stale brew. She was also the owner of a soap factory, by the name of Watson’s Matchless Cleanser. Soap in those days was produced in two-foot-long bars about two and a half inches square. One then cut off a lump as big as they wanted. She also had shares in a factory making towels. Any mis-shaped bars of soap and any ends of towelling off the looms were despatched to the brewery and handed out on request to these night walkers. A piece of towelling and a lump of soap was a king’s ransom for them.

Years ago, there used to be an old hermit by the name of Elijah Rushton who made his home in an old tin shack near the canal bridge at Handsacre. In conversation with my father, Elijah told my father that he walked to Uttoxeter solely to get soap and a towel. I can remember him asking father if he had an old cut-throat razor to give him. He must have been the only man to shave with cold water and without a mirror. It was obvious a hot wash was a rarity to him.

At this time, on my paternal side, a family by the name of Manifold lived on the estate of Osmaston Manor near Ashbourne, then owned by Sir Ian Walker. Our family name was derived from the fact that years before a feudal lord gave them ground by the side of the River Manifold. Originally the name, meaning many folds or fields, was spelled Manefold and many tombs can be seen in Derbyshire with this spelling. This family at Osmaston were like general factotums on the estate. The men folk ran the estate farm and stables. The women ran the laundry. One woman not only ran, but made all the bricks for the estate at the brickyard at Shirley Common.

A small farm became vacant at Yeaveley and my grandfather, William Manifold, asked his lordship if he could have it and still work on the estate farm; to which his lordship said, ‘No, because you are not married.’ Whereupon my grandfather married his woman friend immediately. My grandmother was the daughter of the owner of the Green Man Hotel, Ashbourne. Her father used to drive the rich Londoners who came up to Ashbourne on the mail coach around Derbyshire to see the scenery in his hansom cab.

My grandfather still worked on the estate and ran this small farm. He and his wife worked very hard together and within three years moved to another estate farm, Barn Farm, Stramshall. Here two sons and two daughters were born. My father George was born in 1892. When he was 10, he fell down a ladder and injured his ankle. At this time Sir Ian Walker had become obsessed with the game of polo. He had been visiting the Mountbatten family at Broadlands. He instructed grandfather to make him a polo field at Osmaston. This construction was started at the same time as my father was recuperating from his injury. His father instructed him how to propagate trees from both seeds and cuttings. The field was sown with special grass and special stables were built for the polo horses. In 1904 my father assisted his father to plant 112 trees all around the perimeter of this field, when the grass was established and fit for use. By 1978 Osmaston Manor had been demolished and it was mooted that the Ashbourne Agricultural Show was to be held on this field. Because of my father’s association I was privileged to be escorted around the field by the estate agent. Sadly, there were only 97 trees left and, sad to say, the following year was the last time the Show was held on this field.

At this time my grandfather was negotiating for and was able to buy Boughey Hall at Colton, near Rugeley. It is a farm up the lane by the school. Photos still exist within the family of my father leading a loaded hay cart with a chain horse through the ford at Colton, as at that time the bridge over the stream was so narrow the hubs of the carts used to scrape on the sides of the bridge and this upset the horses. A chain horse was left tied to the hedge ready for the next load.

In 1908 the Blithbury estate came on the market. William Manifold subsequently bought it. My father married Olive Onion in 1913 and subsequently, my elder sister Olive and I were born. Meantime the coffers of William Manifold were getting full and so he purchased Church Farm, Armitage. Here my father and his brother were put in partnership.

This partnership did not last long – my grandfather became greatly disillusioned by his elder son’s behaviour and declared the farm bankrupt when I was seven. In no way would William provide a livelihood for his eldest son again and he went to work at Brereton Collieries. My father obtained a position at Marchington Woodlands. During the short period we lived there, I sat for the County Scholarship at Uttoxeter and passed. The Staffordshire Education Committee considered I was too young at almost ten for higher education and recommended that I sat again the following year.

In the meantime, my grandfather had become very ill and passed away in 1931 – his money making had stood him in good stead as he had to have a private male nurse with him for the last four years of his life. Twice he was taken down to London for serious operations, which we later knew was for cancer of the tongue. It was his wish that my father should move to live in his residence at the Wood House; Blithbury Farm had been given to his eldest daughter, Blanche Godwin. So, we moved to Blithbury.

In recent times Blithbury Farm was sold by my cousin’s widow. Prospective buyers wondered why the acreage was so spread and the auctioneers referred them to me. The reason was that my grandfather realised when another farmer was in financial difficulties and would go along, buy the farm, allowing the farmer and his family to live there. They had to farm under his instruction. When he thought they should be back on their feet, the property was offered back to them at his price. If they could not meet this figure, the farm was sold by public auction and the tenant invariably had to vacate. William made a lot of money by this method. Although it was not liked, he continued and, at one time, owned five farms other than the one they lived in. The first one to succumb was Mr Billy Gildart in Hill Ridware Road.

At that time the Old Swan [now known as Swan Cottage] was to be de-licensed and it was bought for their home together with the small cottage on the end.

Incidentally, many years before, my great-grandmother had assisted a visiting doctor who rode on horseback from Rugeley twice each week to see the sick. It was a great family joke, as she had to pulverise all the herbs the doctor recommended by the pestle and mortar method. For any joint pains, the usual recommendation was camphorated oil embrocation. For coughs and colds, certain herbs together with Ipecacuanha wine made up with water was used. For bronchitis and chest infections, a linseed poultice was always the remedy.

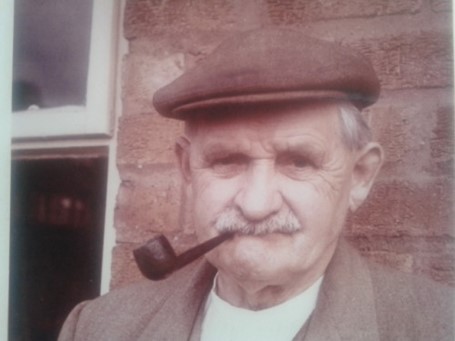

I can remember the cottage at the end of Blithbury Farm Lane being occupied by a family by the name of Mayhew together with nine children. The one up and one down adjoining was occupied by Mrs Mayhew’s mother, a Mrs Walkeden, a dear old lady who lived to be about 100 years old. I can remember her walking up to the Bull & Specs for her half pint: long black petticoats, highly polished high-legged boots and a wonderful lacey poked bonnet. She always had a bent walking stick and never ventured any further into the Bull than the porch, where she and old John Tenney used to reminisce. On our many visits to Blithbury when my grandfather was ill, my father always made a point of taking us into the porch to have a word with these two dear old souls – very fascinating characters.

During my grandfather’s last weeks, we were called to his bedside. On the bedside table was placed one half-crown, one two-shilling piece, one shilling and one sixpence. The four granddaughters were called up according to age: Beatrice Godwin took the half-crown, my sister Olive took the two-shilling piece, Blanche Godwin took the shilling and I was left the sixpence – my only gift ever from my grandfather. This I kept and when I was married my husband had it mounted for me and I wear it on a chain to this day.

My parents remained at the Wood House until 1939. My younger brother Ronald was killed at the end of Stoneyford Lane by an overloaded cattle lorry returning from Uttoxeter market in July 1938. This unsettled my parents greatly. They needed to get away from so many memories, so they took on the licence of the Shoulder of Mutton at Hamstall Ridware, where they remained for 17 years until my fathers’ health failed and they moved to my home at Walton-on-Trent.

Incidentally, William Manifold was a founder member of the Staffordshire Agricultural Society. At the time of his death there were no less than 27 certificates of merit hanging in the house. They were all awards to him for various branches of agriculture. His prowess in the county was greatly recognised and so rewarded. At the time of his death his record had not been surpassed. A special Sheraton cabinet was bought to display all the silverware he had won. This cabinet and all its contents were left to Beatrice Godwin.

It is worth mentioning that the first property sold by Mr George Brown when he started as an auctioneer in Rugeley was the smallholding, the first on the right, down Pipe Lane. It was sold by a family named Richards, and bought by the Plants. I can remember Miss Harriet Plant driving her mother to Rugeley in a governess cart; later this property was sold and bought by the Causers.

One of my abiding memories of Blithbury is the Benton family, who lived opposite the Wood House. They were two brothers and one sister, whose name was Miss Zilla Benton. She was a veritable slave to her brothers. Every three months she used to cycle to Burton to a Brewery for hops and malt to brew their beer. The delicious smell wafting across to home on Zilla’s brewing day was memorable. Every meal time on their table whether it be breakfast, dinner or tea there was a large white pitcher jug of beer. Zilla always brought across a large jug full of her brew every Christmas morning for my father’s Christmas lunch. Zilla maintained it wasn’t Christmas lunch without a drink of home brew.

A great event in my life was a walk with my father through the fields or the woods, because one either had a fantastic nature lesson on the grasses or trees – or a lesson on the birds and animals and their eating habits. Agriculture and evolution were almost always topmost on my father’s mind when taking that walk. I shall always say that he was the cleverest man I could ever meet. He was so knowledgeable and most certainly ahead of his time. He always knew how farm machinery could be improved, but unfortunately never had the money to put his ideas into practise.

I loved life at Blithbury. Our parents were always concerned that we should be educated correctly, well mannered, and always well behaved but always happily. Would that all the families in this day and age had the love and consideration of their parents that we had.

In editing this account for the Ridware History Society website in 2024, we have discovered that it is not entirely clear or accurate in some places. Unfortunately, its author is no longer with us to be consulted, but we feel that it is of such interest and value, that it should be included. Her remarkable memories extend back to the mid-19th century and we are truly grateful to have this insight into Ridware as it was.