Pencil sketch and water colour of Hamstall Mill by William Boden c.1912

Over 30 years ago, c.1988,local resident and amateur local historian, the late Ron Elton, wrote a book on the history of Hamstall Ridware. He wrote of a cheese factory in the village on the site of the old corn mill by the River Blythe, close the Shoulder of Mutton. Speaking to locals, such as William (Bill) Sherratt, and the use of resources available at that time, led him to conclude that the factory had been started at the beginning of the 20th century. Since then, online research, particularly in the newspaper archives, has made it possible to confirm that the cheese factory in Hamstall Ridware had in fact started approximately 15 years earlier, in the spring of 1885.

Traditionally, dairy farming was synonymous with the manufacture of butter and cheese in the farmhouse, the work largely done by the women of the family and by local girls hired as dairymaids. In those days little milk was generally used in liquid form as we do now, so cheese and butter making was the best way of using and preserving excess milk, particularly in the summer months. In the 18th and up to the mid-19th century this artisan way of cheese making was to be found throughout the nation. However, a number of events contributed to the decline in this practice nationwide.

Firstly, the repeal of the Corn Laws in the 1840s moved Britain towards a free trade economy – removing restrictions from import and export tariffs on a wide range of imported agricultural products. By the 1850s cheap dairy produce flooded in to the country, especially from the USA. Wooden hulled clippers designed for speed, were able to carry perishable goods, such as cheese and butter packed in the hold, at first packed with ice blocks, but very soon after with mechanical refrigeration. This influx of cheap agricultural produce led to the Great Farming Depression in Great Britain which lasted from then until the start of the First World War.

Cheese had been produced in America since early in the 17th century when English Puritan dairy farmers brought their knowledge of dairy farming and cheese making with them from the Old World to the New English colonies. Farmers began to see the value of working together and pooling their resources into a centralised cheese processing facility to convert their milk to cheese and other dairy products. In 1851 the first purpose-built cheese factory was established in Oneida County, New York State. This model worked on the principle that ‘there needed to be a new division of employment; the maker and the manufacturer of the cheese and butter needed to be a different person to the provider of the milk’. It proved to be a highly successful enterprise and over 500 identical factories were built across the United States over the next 15 years.

Lastly, in the UK in the 1860s Rinderpest or Cattle Plague, a disastrous cattle disease, seriously impacted milk production and therefore farmhouse cheese production. There was also a contentious assertion that, ‘the decline in making cheese and butter is much due to the fact that over past years there was a growing disinclination on the part of rural women to undertake dairy work’, as was reported in article in the 1867 Bell’s Weekly Messenger which continued, ‘in Britain, whatever the reason, good butter and cheese was insufficient to meet the demands of the consumer’.

So, some 20 years after the opening of the American cheese factory, Derbyshire farmer, miller and dairyman William Gilman, having studied the American success of factory-produced cheese, together with the Honourable Edward Coke of the Longford Estate, Derbyshire, had an exact replica of the New York factory built on the Longford Estate. When it opened in 1870 Gilman became the manager. Over the gateway entrance of the estate were the words, ‘This is the first cheese factory erected in Great Britain’. Here a range of Derbyshire cheddar cheeses were made. Lord Vernon, at nearby Sudbury Hall, quickly followed suit and then other factories in Uttoxeter, Rocester and Croxden in Staffordshire rapidly followed. With improved rail networks and refrigeration systems, milk could be rapidly conveyed further afield in bulk to a central collecting point and then on to nearby cheese manufactories, so it made sense for farmers to pool their milk supplies to send to the factories. During the 1880s there was an almost total abandonment of farmhouse cheese making by dairy farmers living within five miles of a railway line.

The factory system was good for farmers as it broke up the monopoly formerly enjoyed by the cheese factors. William Gilman had once written in a newspaper article, ‘The least necessary members of the body get the largest share of the profit. A cheese factor gets a much larger profit on the sale of the cheese than the maker obtains, when he, the factor, is merely a distributor, and not a necessary one at that.’ (A factor was an agent transacting business for others, in this case dairy farmers or one who bought and sold goods on commission, in this case cheese).

After four or five years’ experience at Longford, Gilman, now a notable cheese manufacturer, became a well-respected authority on the factory system and was involved as an advisor in the planning, building and the setting up of factories across the country. In the mid-1870s there was a mini explosion of cheese factories, with north Derbyshire and south Staffordshire having the greatest concentration of cheese manufactories.

It appears that in rural villages such as Hamstall Ridware, dairy farming families still preferred to produce and sell cheese in the time-honoured way. Even for them though, changes were afoot and some 15 years later they did embrace the idea of using a central cheese-making establishment, albeit on a small scale and in their immediate vicinity.

In 1885 an article was written and published in a number of newspapers as far apart as Scotland and Wiltshire. In December 1885 The Salisbury and Winchester Journal printed the article in full. It was entitled, ‘The History of a Cheese Factory, Hamstall Ridware in Staffordshire’. The report described how, in the spring of 1885, Lord Leigh, who was then the landowner of the Hamstall Ridware Estate, was asked by three of his more influential, larger tenant farmers, namely Henry Jaggard of Hamstall Hall, William Lawrence of Rowley Farm, and William Carrington Smith of Rough Park, if he would entertain the idea of finding a building which could be used as a cheese factory. The answer was in the affirmative.

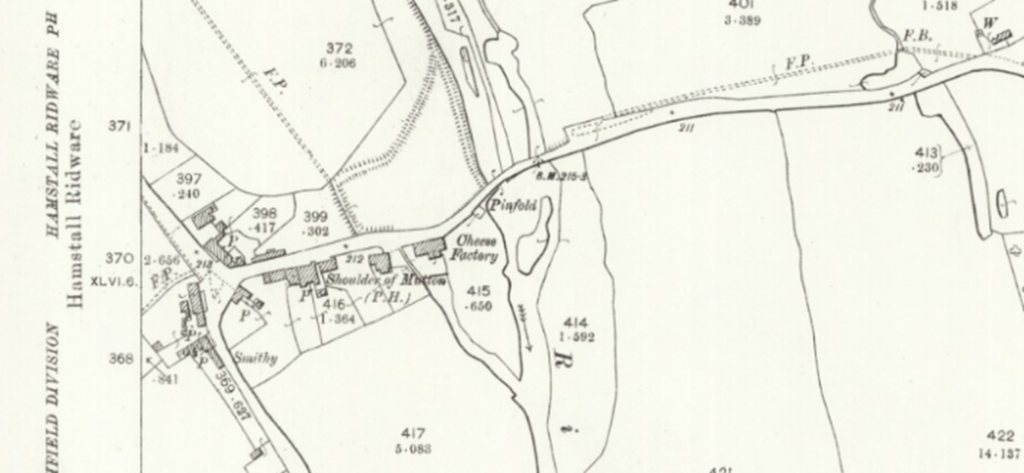

On the 1871 census there was a miller, Jonas Phillips from Devon, living at the Mill House with his family and on the 1881 census he is still recorded as miller. However, in 1885 Lord Leigh granted the three farmers use of the flour/corn mill on the banks of the River Blythe, near the Shoulder of Mutton public house, so it must have ceased working sometime between 1881 and 1885 for it to have been available.

The business was set up and managed by a committee, including the farmers who had instigated the scheme and who had incidentally, previously worked as the ‘cheese factors’ that Gilman had written so scathingly about. In October 1887 a receipted bill was sent to Lord Leigh from Frank Orgill, (Secretary, Hamstall Ridware Dairy Association) ‘in respect of the cheese factory water supply’.

The 1885 newspaper report stated that:

New floors and much necessary building work was done by the landlord but the tenants, Messrs Jaggard, Lawrence and Carrington-Smith supplied the engine, vats, tanks, pipes and other fittings. The ‘factory’ which was capable of handling milk from around 500 cows, was supplied with milk from local farms. The first cheese was made on 4th August and the last of this first short season, on 1st November, the total number being 400 cheeses and the total weight about five tons. The cheese making was done by a man and his wife. Out of the cheese making season the husband was to be employed by the managers on other farm work…The cheese made at this factory was, by a large buyer of factory cheese, pronounced to be the nearest approach to home-made Derby cheese of any factory he has seen.

Who the original couple in the report were may never be established. What is known is, that a young couple, John Thomas Lomas Phillips and his wife Hannah Lowe Phillips from Alstonefield on the Derbyshire/Staffordshire borders, plus their three very young children, were certainly recorded as living at Mill House in Hamstall Ridware on the 1891 census and his occupation was ‘dairyman’. (These Phillips were no relation to Jonas Phillips who was the previously mentioned miller.) John and Hannah were married in Alstonefield in early 1887 and their first child was baptised there later in 1887. John’s occupation was described as ‘assistant in cheese factory’. Their next child, Eleanor was born on 8 January 1889, her birth being registered in the January/March quarter of 1889 at Ashbourne, so it seems unlikely that John and Hannah were the man and wife referred to in that 1885 report. As their third child was born in Hamstall Ridware in May 1890, John and Hannah must have come to Hamstall Ridware between March 1889 and May 1890.

An article published in the Staffordshire Advertiser in 1961 seems to confirm the timeline. A daughter of John and Hannah, Eleanor Gould (née Phillips), told of a letter found in ‘family papers’. It was headed Hamstall Hall and had the date March 6 1889. It was addressed to Mr Gilman (of the Longford cheese factory), from the then tenant farmer, Mr. H.R. Jaggard:

I am writing to ask you if you can recommend us [i.e. Hamstall Ridware cheese factory] a young man who could undertake to make us the cheese from 70 cows to start with (in summer months it might reach 100). Mr W.C. Smith whom you know (from Rough Park) is sending his milk to Birmingham this year which has disarranged all our arrangements. We do not want to pay too high wages as the number of cows are so small at the beginning; but still, if he would make us a good lot of cheese we should be glad to make it worth his while to do so. Eleanor Gould said, ‘It is 73 years since my father came as manager of the cheese factory here and eventually bringing the family over’. She recalled when she was a little girl, ‘carrying many of the old Derbyshire cheeses my father made at the old mill to the drying rooms. He would make 30 a day and it was my job to stack them on the shelves.’

John Phillips had not been brought up in the agricultural world. He was born in 1863, the illegitimate son of a Sarah Phillips. They lived with his widowed grandfather, who was a shoemaker. The fairly new Hopedale and Reapsmoor cheese factories, both in the parish of Alstonefield, would have needed local workers at a time when John was of an age to have been looking for employment, so he could have served an apprenticeship at either of them. Later as an experienced cheese maker, he may well have come to William Gilman’s attention and been recommended as a suitable employee for the Hamstall factory. Hannah’s father was himself a farmer, and could well have influenced the young couple’s decision to come to Hamstall Ridware.

In an earlier interview reported in the Lichfield Mercury in 1949, Eleanor said that her father had manufactured a range of Derbyshire cheddar type cheeses rather than the Staffordshire type, and these were sold as far afield as the Goose Fair at Nottingham. The enterprise must have been a success as in May 1892 the Warwickshire Chamber of Commerce held a meeting in Warwick Shire Hall to discuss the feasibility of setting up similar cheese or butter factories on Lord Leigh’s Stoneleigh Estate, citing the success of the factory on his Hamstall Ridware Estate in Staffordshire.

However, things obviously didn’t continue quite so successfully, as just over a year later, a newspaper article in June 1893 reported that the factory had closed. This must have been because of long standing problems, first reported on in 1882 and 1884, of a poor drainage system that was unable to cope with the effluent from the butcher’s shop. Obviously, this had been further exacerbated by an influx of whey from the factory combining with already stagnant water lying in, what was known locally as ‘Mitherums’, thus causing a health risk, the risk of typhoid being a very real fear. Mitherums Croft was described as ‘a yard’ opposite the Shoulder of Mutton, probably on the site of the filled in mill pond. The closure must have only been temporary, as an entry in Kelly’s Directory of 1896 still lists Frank Orgill as the secretary of the cheese manufacturers at the cheese factory and the same trade directory of 1904 still cites John Phillips as the manager of the Hamstall cheese factory.

There appears to be further confirmation that cheese making had continued or resumed, if only in a limited way. In July 1909 the Walsall Phoenix Cycle Club had been exploring the local area. A write up of their visit was printed in the Walsall Advertiser:

…having come from Alrewas and taken a wrong turning, they arrived in Hamstall Ridware coming via the bridge over the River Blythe, whereupon they came to a building by the river where several carts were emptying cans of milk into a large tank, which was afterwards weighed. Enquiries proved the place to be a cheese factory. It was the only industry in this little village, and the manager of this small factory kindly consenting to show the members of the cycling club round, who were very much interested in the different processes of cheese making.

This is the last definite reference to the Hamstall factory still being in operation that has so far been found. Countrywide, after the initial enthusiasm, the success of the small dairies and cheese makers was varied. Some had difficulties in making a profit even in the early years and by the turn of the century, most of the little cheese factories were finished. Of those who had struggled on, many closed before the First World War as a result of competition from milk contractors.

An advertisement in a 1910 edition of the Derbyshire Advertiser stated, ‘F. W. Gilbert and Co. are open to purchase large or small dairies’. So presumably this is what happened to the factory in Hamstall Ridware.

On the 1911 census John Phillips is recorded as grocer and corn dealer, and no other person enumerated as a cheese maker or dairyman, the cheese factory is empty and John Ashmore, a butcher, now lives in the Mill House next door.

The 1912 Kelly’s Directory lists F.W. Gilbert and company of Derby, as cheese manufacturers in Hamstall Ridware, although there is no evidence that cheese was being manufactured there. At this time there were four large dairy companies in the region who were in the habit of buying up small manufacturing concerns in order to wind them down, but continued to collect the milk to transport to their larger cheese factories or creameries.

Gillian Barnes, granddaughter of John Philips told me that her mother, a daughter of John and Hannah, remembered milk in large churns being delivered to the ‘milk factory’ from local farms to be transported somewhere else. This confirms what Ron Elton had been told by some of the oldest residents who had recalled the place being called the ‘milk factory’.

In 1920 John Ashmore bought the near derelict building when Lord Leigh sold off some of his Staffordshire Estate properties to his tenants. It was advertised as a cheese factory. In 1921 the property was being sold again on behalf of John Ashmore, deceased. At least twice more, in February 1922 and November 1923 it was advertised for sale as being, ‘suitable for a milk collecting place or cheese factory for the manufacture of surplus milk’. In the 1961 newspaper interview, Eleanor Gould concluded by saying, ‘At the finish my father bought the factory with all the stock and it is still in the possession of the family today.’

In his book Ron Elton says that Herbert Phillips, a son of John and Hannah, owned 22 acres of land by the River Blythe and the disused mill/cheese factory where he kept Friesian and Jersey cows and operated the old mill building as an attested cowshed. I.e. a place where cattle could be certified as being free from a disease, especially from tuberculosis. Herbie, as he was known, had told Ron that he had found and kept his fathers’ pencilled notes which had been pinned to the walls of the upper floor of the building. These notes detailed customers’ names, weights of cheeses and railway stations to which they were to be sent. Gillian Barnes also remembers these but doesn’t know what happened to them.

In June 1961 the ‘20 acres of land and farm building used as a hay barn at the side of the River Blythe’, was advertised for sale by the Trustees of H.H. Phillips. Local farmer, Mr Cyril Croxall, bought it, but as so often happens with agricultural buildings, it became rather neglected and over time fell into disrepair. He sold it to a speculative builder in 1982, thus began the final chapter of Hamstall Ridware Mill. The building was virtually dismantled and rebuilt as a private house, using as much of the original materials as possible. For a time, Jill Cox, a member of Ridware History Society, lived there.

1969. Old Mill building when it was used as a hay barn.

Author: Helen Sharp

Sources

- Elton, Ron. Hamstall Ridware: A village of Staffordshire (1988)

- Taylor, David. Growth and structural change in the English Dairy Industry c1840 – 1930 in Derbyshire and Staffordshire (1987) Research Gate accessed July 2021

- British Newspaper Archive accessed 20 May 2021

- Shakespeare Birthplace Trust accessed 20 May 2021

- Historical Trade Directories accessed 20 May 2021

- National Library of Scotland accessed October 2019

- Mills Archive accessed July 2021