If only walls could talk…

In Hill Ridware, tucked down Wade Lane, which was anciently called Watery Lane on account of its propensity to flood, stands a red brick Georgian house built between 1790 and 1800. It was reputedly built for Charles Chadwick, the Lord of Mavesyn Ridware Manor, as a ‘Hunting Box’; that is a house used as a temporary residence in the hunting season. At this time the house was known by the seemingly grand title of the Upper House, although this probably was simply because it was on much higher ground than the Manor Hall in Mavesyn Ridware. When Charles’s son,Hugo Mavesyn Chadwick, married Eliza Catherine Chapman in 1826, this became their family home. They may only have occupied it for a short time, as Hugo’s father Charles died in 1829, and thus Hugo inherited New Hall in Sutton Coldfield as well as the manor of Mavesyn Ridware. When he and his family were not in residence at the Upper House it was rented out to members of the upper echelons of society. Hugo died in 1854 and his wife Eliza and daughter Catherine moved back to the Upper House in 1856, remaining there until Eliza’s death in 1868.

From then on, the house ceased to be occupied by members of the Chadwick family, being let to the likes of JPs, industrial entrepreneurs and to high-ranking officers of the army and their families.

Around 1896 the Upper House became known as Ridware House.

A family of particular interest lived there for two decades, from just before the outbreak of the First World War (1912/13 until 1934). This family was Paul Rycaut Stanbury Churchward, his wife Ooryala Mary Donisthorpe and their only son, Paul Robert de Shordiche Churchward. Paul Churchward senior, or PRSC as he was often known, was born in 1858 on the island of Malta. He had a distinguished military career in the British Army, beginning his service in 1878 as transport officer in the North Lancashire Regiment. He served in the Afghan War of 1877-1880, for which he was awarded a medal and clasp. In 1879 he was promoted to Second Lieutenant. He took part in the Bechuanaland Expedition of 1884 -1885 as a special service officer. He was promoted again to Captain in 1886. He served in the South African War (Boer War) of 1899-1902 as Major of the 1st Battalion of the North Lancashire Regiment, participating in the defence of Kimberley. He was mentioned in despatches and given the brevet of Lieutenant-Colonel. For his services he was also awarded the Queen’s Medal with four clasps and the King’s Medal with two clasps. In 1909, now a Battalion Colonel, he completed his period of service aged 50 and was placed on the half-pay list and seconded to the War Office. From 1January 1910 to the 31 December 1911, he held the Command of 13th Middlesex Infantry Brigade – Eastern Division. Subsequently he was invested as a Companion, Order of the Bath (CB) in King George V’s Coronation Honours List in June 1911 and awarded the DSO. In 1912 he was offered what his son Paul, later described as in military parlance ‘a plum job’ as Brigadier Commander or Brigadier Major of Northern Command No. 6 District comprising Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, Rutland, Staffordshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. His base was Lichfield Whittington Barracks and in December of that year he, his wife and five-year-old son moved into Ridware House, Hill Ridware, to live in semi-retirement. Then in 1914 war was declared in Europe.

At the age of 55 PRSC could have remained living in safety at Ridware House for the duration of the First World War, but having had a long army career he felt he should return to the active list, which his grandson Robert wrote was, ‘against Lord Kitchener’s advice’. In 1915 he took command of 126th Brigade in the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign. He sustained a wound necessitating a stay on a hospital ship, but what nearly killed him was contracting dysentery. He was sent home to get proper treatment and made a full recovery. He was awarded a Silver War badge in 1917 when he finally retired. His family believed that, had he stayed on in his Home Command position, there is little doubt he would have reached full General or higher and been awarded a Knighthood.

Now fully retired, PRSC, with his wife, as the occupiers of Ridware House, took seriously their responsibilities as honorary ‘Lord and Lady of the Manor’. They fully immersed themselves in parish life, attending various functions such as the flower shows, school concerts and participated in fund-raising fêtes and garden parties, hosting some events at their home. In 1919 it was PRSC who paid for the war memorial tablet in Mavesyn Ridware parish church and donated generously towards the welcome home dinner at the Chadwick Arms and thank-you gifts for the returning service men and women, which were presented by Mrs. Churchward. (At least three women are mentioned in a newspaper report, unfortunately not named)! The ex-soldiers each received a silver cigarette-case, richly engraved, and bearing his monogram, and the dates 1914-1918 and each of the W.A.A.C.s received a silver wristlet watch, also bearing her monogram and the date’.

From his memoirs, it is obvious that their son Paul Robert de Shordiche Churchward, affectionately known as Bob, grew to love his new home. As an only child of a Colonel and high society mother, it was natural that he would be enveloped by the adult world; his parents often entertained the local ‘big-wigs’ and members of the army hierarchy, such as Lord Kitchener, were frequent visitors. Not many boys would have had Lord Kitchener explaining battle tactics to them:

I became conscious of a presence standing over me and looking round I saw K was casting an eye over my far-flung battle line; as I looked up, he gazed down at me and said ‘you will never do any good boy until you learn to keep your cavalry on the flanks’.

However, what Paul junior liked to do best was to decamp into the world of the servants or go exploring his environs looking for adventure: I sought the earliest opportunity to make my escape from the dining room or drawing room and slip unobtrusively through the heavy swing door and cross the dividing line between what was known as the ‘front’ into the ‘back’. It was only then I could relax and begin to feel really at home. Life in the servant’s hall was far livelier and more enjoyable. I soon struck a firm friendship with the boy whose main job apart from cleaning all the boots and shoes, seemed to consist of trimming and filling a vast array of oil lamps. As soon as I was able, I would escape the day nursery to go to the stables.

In those days it was only natural and even expected for a young boy of his class to be inducted into the world of fox-hunting. So ‘Master Bob’ would go with his parents who rode out with the Staffordshire Hunt. Initially he shared their passion and enjoyed the ‘thrill of the chase’.

In 1918 or 1919, aged about 11 or 12, Paul had a brush with death when he caught Spanish flu. In order for him to recuperate, the family moved to the Devonshire coast, where they lived for about a year.

Like his father, Paul went into the armed forces. He was commissioned in 1926 in the service of the Royal Norfolk Regiment and gained the rank of Lieutenant in 1929. He resigned his regular commission in October 1930.

In June of 1931 Paul, who had never lost his sense of adventure, had been to Brazil and explored parts of the Araguaya River; however, he contracted cerebral malaria and on his return was confined to hospital for four months between October 1931 and February 1932. This did not dampen his enthusiasm for ‘derring-do’ as evidenced in a report in the Lichfield Mercury in June 1932. The headline read ‘A Risky Trip – Hill Ridware Man to Visit “River of Death”’. The background to this trip was the following fascinating story.

In 1925 Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett had embarked on a journey into the uncharted heart of Brazil, the Mato Grosso, reportedly in search of El Dorado. He never returned. Fawcett didn’t believe in a lost city of gold, but he did have a theory that El Dorado wasn’t completely a myth. He thought that the story might be based on a real city that existed deep in an uncharted area of the Amazon rainforest. For lack of a better name, he called this city ‘Z’, and if anyone could find the lost city, it was Fawcett – who was already a famed explorer and surveyor with a half-dozen trips through the Amazon under his belt. He had also served as an artilleryman in the British military, fought in the First World War, and worked as a spy in Morocco. So, when he stumbled upon an 18th-century document in the National Library of Brazil written by a Portuguese explorer, who wrote of an ancient city deep in the jungle, he knew that he had to find it.

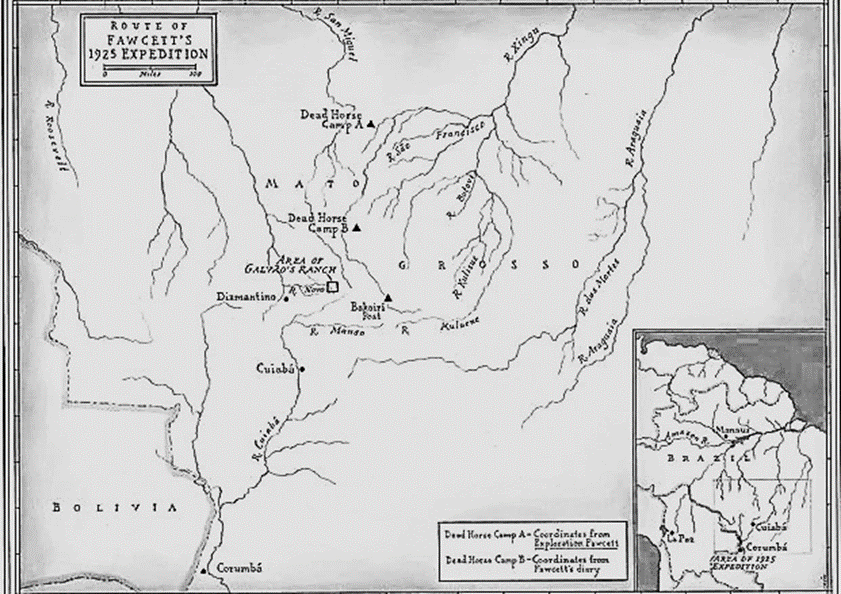

He made his first expedition in 1920, but the death of his horse (hence the name Dead Horse Camp; see map below) and serious illness forced him to abandon the attempt. Five years later, he embarked on his mission again. This time, he took along his son Jack, and Jack’s best friend. Fawcett hoped that by only bringing two people with him, he would be able to travel light and slip past any hostile tribes.

Fawcett planned the expedition meticulously, yet prior to departure issued an ominous instruction to those he was leaving behind: ‘I don’t want rescue parties coming to look for us. It’s too risky. If with all my experience we can’t make it, there’s not much hope for others. That’s one reason why I’m not telling exactly where we’re going.’ He even gave two sets of misleading co-ordinates for Dead Horse Camp. (marked Dead Horse Camp A and Dead Horse Camp B on the above map).

The trio set out into the rainforest and in April, the party left the Brazilian city of Cuiabá, one of the last outposts of civilization in the Amazon. In late May 1925, Fawcett wrote a letter to his wife from an encampment he had created on his earlier expedition, reporting that things were going well and assured her that success was close at hand. This was the last message anyone ever received from him.

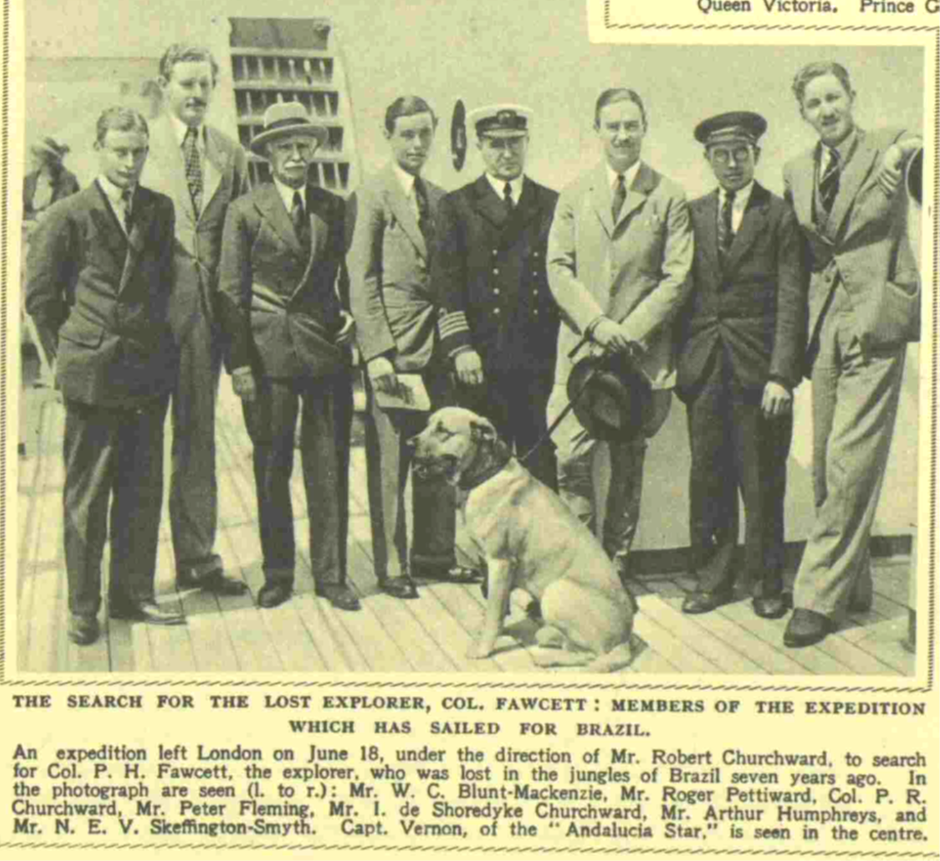

The Fawcett expedition had not been expected back until 1927 and after a further period of about three years, it was widely accepted that the party was dead. However, with no proof of this, theories were expounded and rumours began to circulate about what might have happened to them. Despite Fawcett’s exhortation that no one should search for him, over the next four years a number of search parties did set out to try to discover the truth without success. Stories fuelled further speculation. One was told by a Swiss trapper, that he had spoken to a white man held captive by an Indian tribe. Other sorties spawned the idea that he had become a willing dweller in the Brazilian jungle. The most commonly held belief was that the group had either died of a tropical illness or been murdered by the ‘savage natives’. At this point the intrepid Paul Robert de Shordiche Churchward decided to enter the fray. He put a small advertisement in the personal column of The Times asking for volunteers to join him in a quest to discover the truth of Colonel Fawcett’s disappearance. One respondent was Peter Fleming (brother of the writer Ian Fleming), a distinguished member of The Times newspaper editorial staff. Other members of the party included Paul Churchward’s father, Colonel P.R.S. Churchward, and Arthur Humphries, the Churchwards’ chauffeur from Hill Ridware Hall.

On 18 June 1932 the group of eight boarded the Andalusia Star at the Port of London, bound for Buenos Aires.

Their mission was threefold: to search for traces of Colonel Fawcett’s party; to explore and map the Mato Grosso and the Rio das Mortes (River of Death); and to discover the mineral wealth of the jungle. It appears from newspaper interviews that Paul didn’t expect to find Fawcett alive, but hoped to establish what had happened to him and his party and quash rumours of their survival once and for all. On his visit to Brazil a year earlier, he had discovered evidence of minerals, ‘Perhaps greater than in any other region of the world – It is just there for the finding. We shall certainly look for traces of gold and diamonds.’

In the event, his father fell ill on arrival and perhaps fortuitously at the age of 73, had to remain in Buenos Aires for the next five months. This was not really an expedition for the elderly!

A rather scathing comment on Wikipedia states that:

Despite a great deal of fanfare, the expedition was poorly organised. The group didn’t seem to have done much in the way of preparation, not even bothering to learn Portuguese.

Not that that would have been much help as the indigenous people they were likely to encounter had their own languages.

An article written by Peter Fleming in The Times shortly before the expedition set off indicated that that critique was a little wide of the mark. Obviously, Paul Churchward’s reconnaissance of the region a year earlier would have been a big advantage. He had also closely studied written evidence from various expedition leaders over the previous seven years to learn of potential pitfalls. Although he was regarded by his comrades as their leader, Bob or Robert as they referred to him, in recognition of his own limitations, had enlisted the help of someone else to co-lead; Captain John G. Holman, a British resident in Brazil, whose knowledge of the interior was deemed to be ‘equalled by few white men’. Roger Pettiward and N.E.V. Skeffington-Smyth were to undertake surveying and mapping the area and N. de B. Priestly was to make a photographic record. The inclusion of the chauffeur, Arthur Humphreys, was because of his knowledge of mechanics which would be useful to maintain the outboard motor, used when navigating the rapids.

The plan was to proceed up country from São Paulo by train, by motor-lorry and if necessary, by ox-wagon. Once at the Rio das Mortes they would embark in bataloas, long canoes used by the Indians of the Araguaya. They were to push as far up the river as rapids and Indians would permit and form a standing camp. Again, a later report indicated that the party had a ‘falling out’ and split up – yet the plan outlined in Peter Fleming’s article showed that they had always intended to diverge.

With this camp as a base, it is hoped that it will be possible for a small “storm detachment” to strike Westwards on foot over the 200 miles or so of entirely unknown country…It is in this area that traces of Colonel Fawcett’s presumably ill-fated expedition are most likely to be found.

The expedition was to be heavily armed but ‘will be at pains to avoid all aggressive action… Mr. Churchward is taking out with him several bows each with 52lb pull and .22 rifles’. After a trek of some 1,500 miles and many trials and tribulations, illnesses and some humorous escapades, in November 1932 the party returned to England not having found any proof one way or another with regard to Colonel Fawcett. The expedition had cost about £3,000, nearly a quarter of a million pounds in today’s money. They had had a great adventure but practical results were few, although they had collected some valuable data for future exploration and mapping of the territory.

In 1936 Paul Robert de Shordiche Churchward wrote and had published a book called Wilderness of Fools and Peter Fleming wrote a book called Brazilian Adventure based on their exploits. It has been mooted that themes in the Indiana Jones films were based on the Colonel Fawcett mystery and the Churchward search. Conan Doyle’s The Lost World is also thought to have been inspired by these exploits.

Shortly before the expedition in February 1932, Paul’s mother, Colonel Churchward’s wife had died. After their return from Brazil the Colonel put Ridware Hall up for sale and moved out in 1934. He died just a year later, shortly after Paul got married in 1935. In the Second World War he resumed his military career, but because of the malaria he had suffered from, did not pass the medical board to be placed on active service. His son believes he may have gone to France during part of the ‘Phoney War’. His records show he was a Captain in the Coldstream Guards and that he served with the Shropshire Yeomanry Cavalry.

During the 1950s he was Master of the Hounds for the South Shropshire Hunt before doing a volte-face and becoming an active member of the League Against Cruel Sports. He was elected Chairman of the Co-ordinating Committee for the Control of Field Sports in the 1960s. He wrote a number of books and newspaper articles against the practice of fox hunting. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

Despite a couple of close encounters with death when a child and then a young man, Paul Robert de Shordiche Churchward died in 1981 at the age of 74.

Sources

- Extracts from Memoirs of Paul Robert Churchward kindly shared by his son Peter Robert Churchward

- British Newspaper Archives on Find My Past

- The Times Newspaper Archives

- David Grann The Lost City of Z

Dear Ms Sharp

I’m researching the life of John George Holman, the notorious ‘Major Pingle’ of Fleming’s ‘Brazilian Adventure’ and also of Churchward’s counterblast, ‘Wilderness of Fools’. As you know, when the two parties reached Belem they gave very different accounts of events. According to Sir John Ure (‘Trespassers on the Amazon’, 1986, available via Internet Archive) Holman with the help of three other members of the party who were ‘loyal’ to him — (Churchward among them I take it) — prepared his own version of the breach and the reasons for it. Ure saw this account in Sao Paulo, and quotes extensively from it in his book. I’m guessing he would have seen the document some time in the early 1980s; as far as I know it has never been published. I’m wondering whether there may be a copy somewhere among Churchward’s papers. Can you cast any light?