From interviews and conversations over a period of time from c.1997 to 2023

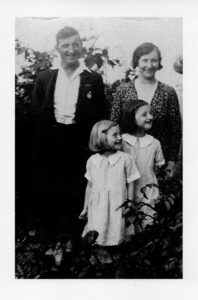

Joyce thought this photo must have been taken not long before her sister Beryl died. She thought it might even have been before the Coronation party.

Joyce was born 22 November 1927. Her parents were Frederick and Lily Knight. Her father was born at Blithbury in the house called Rose Cottage, on the left side, past Mellors’ farm. Her mother, who was a Dale, was born at Longdon, one of about 10 children.

Joyce was born in the second council house, just after the Village Hall. They moved to live in houses known as The Row when she was about two. The houses belonged to the brewery and they were on land beside the Chadwick Arms. There were four houses joined together with a wash house in the middle, with a copper, a sink, a mangle and a cold water tap, which all the families had to take turns to use. Halfway up their family’s garden, there was also a pump. The garden was quite long. This is where her father grew vegetables and there were a couple of fruit trees too. These houses consisted of one room on the ground floor with a scullery and a pantry. There was a black range grate for cooking. Upstairs there was one bedroom and a landing room. The stairs led straight into this room where Joyce’s brother’s bed was. Away from the house at the back were the toilets. There were two toilets together with wooden seats, shared by the four families. In front of the house was a large garden, and a hawthorn hedge with a dent in the middle where her father rested a bowl of water to wash himself when he returned from work. In The Row lived Mr and Mrs Foster on the far left; Emmy Goring with her mum Mrs Downing and also Bernie, who is Nora Downing’s father; then there was the wash house in the centre; then Joyce’s family; and finally, an old man and woman named Mr and Mrs Sammons at the end. These Sammons were the parents of Gladys Johnson’s (née Brown). The Row was demolished around 1960, the houses having been condemned and Chadwick Crescent was built on the site.

When she was perhaps three or four, her father had tuberculosis and was in a sanatorium. Realising that money was probably short, the headteacher’s daughter, Miss Smith, came and gave her mother some malt extract [Virol] for her and her sister Beryl. There were no handouts as there are today, and the poverty was hard. What you hadn’t got, you couldn’t spend, could you?

Joyce’s father was a miner, working at Brereton Colliery. Later he worked for the County Council as a road worker. He would cycle from Hill Ridware to Stafford and then do a day’s work. They might go anywhere in Staffordshire, cycle and do a job, and then come back again at night.

When she was perhaps four, she would go across Pipe Lane from her house in the Row to play outside the school, hoping to see her friends.

Joyce’s mum used to help out when mothers were going to have their babies. She remembers being ‘scooted off’ to stay with her aunt, Alice Berkshire, sometimes for the night when ‘Mrs So and So was due to give birth.’ The District Nurse would be fetched from Armitage, but if she was not available, then Joyce’s mother would deliver the baby. She also sat with people who were dying, and laid them out afterwards. The doctors were in Yoxall and Rugeley.

Three cottages stood by the edge of the road to the left of the Royal Oak, and to the right there were six more houses. Her aunt Alice and William Berkshire lived in one of these cottages on the main road, opposite the School House. Before Joyces’ time one of the houses had been a Post Office and shop. You could still see where the letter box had been. The school mistress, Miss Dutton, lived next door. These were partly pulled down in the 1970s.

The milk was collected in a can from Miss Derry’s farm, on the other side of the Chadwick Arms. When Joyce fetched the milk, she would watch the warm milk pour down ‘the cooler’ into a churn. Miss Derry’s cows were taken from the farm daily, past Joyce’s house and into the fields, through a gate to the left of Avondale. These fields are where the garages in Chadwick Crescent now stand. They grazed on the moors.

Miss Derry’s father, Mr Fred Derry, also was the undertaker. He made the coffins in a building on the right-hand side of the farmyard and Joyce was fascinated by what went on there but her mother did not think it ‘proper’ for her to watch. In 1937, Joyce’s sister Beryl died when she was only six. As little girls they used to sleep in the same bed. She vividly remembered waking up one morning to find Beryl missing, only to discover her in her parents’ bed, Joyce thought she must have had a nightmare. That was the last time she saw her. Joyce went off to school as usual, but when she came home, she was told that Doctor Armison, from Yoxall, had been and sent Beryl off to, she thought, either Yoxall Cottage Hospital or Burton-on- Trent hospital. Joyce was sent to stay with her aunt Alice. Shortly after she learnt that her sister had died from peritonitis. Mr Derry made the little wooden coffin. She recalled that on the day of the funeral the teachers and children from school lined the road as the shellabier [hearse] drawn by small horses went from their house. The bill for the funeral came to £5.6s.0d

Miss Derry and other women from the village caught the bus to market every week.

Opposite the Royal Oak was the blacksmith and a little shop owned by Mr West. Horses came from villages around to be shod. Joyce spent many hours as a child watching the blacksmith at work, with the glowing fire, hot pokers and metal, and the hammering on the anvil. Mrs West also sold sweets and cigarettes and they made ice cream. Joyce’s interest in her father’s and brother’s cigarettes was trying to make up sets of cigarette cards, which were in every packet. Some sets of cards she still has. Eventually, Mr and Mrs West had a petrol pump outside the blacksmith’s shop.

There was a shop opposite the Chadwick Arms at the house on the corner, run by Mrs Eliza Causer, where you could buy tea and other essentials. There was also a post box in the wall. Further down the road at the end of Wade Lane, was the Post Office, run by Mrs Woodvine, which sold dog licenses, stamps, stationery, sweets, groceries and other things. Letters were delivered by Mr Woodvine on his bicycle. This is now Briar Cottage.

There was a fruit cart which came round selling fruit and veg. It came from Armitage. Carthys in Armitage delivered meat. If they delivered a joint of lamb to Joyce’s family, that was it, and they ate lamb for a week. There were also pigs being killed in the village as lots of people had pigsties. They would make their own brawn and various pieces, including pork pies. Joyce’s mother always had pork pie for Christmas breakfast, but Joyce did not enjoy it. There was no turkey at Christmas in those days, but they would have a chicken or a

cockerel, and people also ate pork.

Birthdays really were not celebrated. There were no birthday cakes or other treats and they might just receive a card, which was more like a postcard with a celluloid frontage and a little verse. Not like today, when people go over the top!

Once a year Mrs Sharples organised a theatre trip to see the pantomime in Hanley or Birmingham. To Joyce, that was absolutely wonderful – to go on the coach to Birmingham and sit and watch the show. At the end of the evening, she always felt like crying because it would be another 12 months before they could go again. She remembers seeing Dick Whittington and Jack and the Beanstalk. The stage was so beautiful.

Sometimes they went to the cinema in Rugeley, which was then opposite the Town Hall. Her mother would only take her to see things like Shirley Temple films. It was a one-off treat to go and see something like that. In the Sunday School a man came with a projector and would show mostly animal films and maybe Tarzan. There was also a cinema show, maybe once a month in winter, at the old school. But mostly the entertainment centred around the church, with plays put on by the congregation.

She never went away on a holiday until she was 15, when six girls went to Towyn, near Rhyl. They travelled by train from Armitage to a chalet. They enjoyed the beach, but mostly were longing to get home to have a decent meal. They missed their mums and there was a horrible range thing in this chalet that they couldn’t get to cook properly. She can remember coming home, and oh, to have a cup of tea made by her mum…she learned to appreciate her then.

She had travelled twice previously by train on school trips. They were out of this world. One was to Liverpool, then on to Morecambe Bay and then on a boat trip on Windermere. All in one day! The other trip was to London, when she was about eight or nine. She remembers being by Buckingham Palace and running across the road, when her little case came unlocked and all her bits and pieces dropped on the floor. She commented, ‘Isn’t it horrible when you remember the things that went wrong?’ She thought she was well-travelled. Her parents had never been to London.

On Sunday School trips they would travel to Milford on a bus and climb the hills. Again, they thought it was out of this world! There was a tea room there in a wooden hut and they would have a nice tea after they had played. And that was their Sunday School trip.

The children played in the fields called the ‘Water Forest’, where now stands Mavesyn Close. She did not know why it had that name: there were woods and hedges. A stile at the top of Church Lane enabled anyone to walk across to Ridware Hall.

Quinton’s Orchard was then owned by the Woolleys. The children played on the moors, going out towards Quinton’s Orchard, but that was a little too far. Their parents told them not to go too far. She played with her cousins and also with friends from school. Some of her school friends came from Handsacre. They played ball games and there was skipping and hoops and spinning tops – little wooden tops that you whipped. Colours were drawn on the top with crayons to make it look pretty when it was spinning. There were marble games too. Inside, they liked doing puzzles. They didn’t have a lot but Joyce’s cousin had one of a woodland scene with gnomes and elves and toadstools which they must have done hundreds of times. It was quite tricky, but they never got fed up with doing it. During winter, in the evenings, her father would see her across the road to play with her cousins, and then fetch her back when it was time for bed.

The Chadwick Arms sign stood in the centre of the road and was surrounded by white palings.

Fairground rides were put in the car park of the Chadwick Arms for many years. The fair was run by gypsy travellers. They had dobby horses, which went up and down, and swinging boats.

Wade Lane Farm was owned by Mr Billy Froggatt, Richard’s grandfather. From Wade Lane into Uttoxeter Road were four houses owned by Mr Froggatt where his workmen lived. He also owned three more houses called ‘The Orchard’. They were demolished and the site is now a small development called Orchard Court. Mr Froggatt’s cows came daily down Wade Lane, by the Post Office and into the fields by The Orchard.

Joyce went to the village council school, Henry Chadwick, in what was then called Pipe Lane (as all the village children apart from the children of the ‘rich farmers’ did). The headmaster for the village school, Mr Smith, lived in the house owned now by Mr and Mrs Atack. This was the schoolmaster’s house for the ‘old’ school on the Uttoxeter Road. The other two village school teachers were Miss Balance and Mrs Stokes, who were sisters and lived in Rugeley. Children stayed at the village school until they were 14 years old, but by the time that Joyce was 11, in 1939, Aelfgar School was built, so she went to Rugeley on the first day it opened. It was then called Rugeley Secondary Modern.

A celebration party for the Coronation of George VI was held in Froggatts’ granary in Wade Lane. She had a new frock for the occasion in red, white and blue. They went upstairs to the loft for food. There were also parties at the school. She cannot remember any celebrations for VE Day. So many of the village boys, and women too, were out abroad in the forces. The Froggatts also had Coronation party for Elizabeth II.

When Joyce was about 12 years old the family moved into a new house at the Lichfield end of the village. The house was 7 Ridware Road, a council house, which had just been built. Shortly after they had moved in, she came home from school one day to find electricity had been connected to the house and for the first time her family had electric lighting. Before that they used oil lamps, paraffin lamps and candles to light the house. When interviewed, Joyce still had the paraffin lamp used in that house.

When still a girl, Joyce joined the local women’s football team, playing right wing. They used to play in fields at Rake End.

The Tenney girls, Ginny and Amy, lived at the Bull and Spectacles at Blithbury with their father, who was very strict. He had a large collection of toby jugs, which the daughters broke after his death and buried them in the ‘Smelly Pit’. One of the girls fell in love with someone not considered suitable, so she went off with him and got married, and then calmly went back home. The Tenney girls went to a private school in Mavesyn Ridware at the Rectory, run by the Misses Harvey.

Most people in a little village like this went into service. There wasn’t the means of getting to distant work. Only by bicycle. Some did travel; for example, Margaret Barret went up into Derbyshire. Joyce’s mother and all her sisters worked in the Birmingham area. They would live in, as maids in big houses. Joyce believes that the people her mother worked for were theatre people and it may have been in Edgbaston or Erdington.

Joyce also had an older brother, Harold, who served in the Second World War. First, he was at Whittington Barracks, and then was sent to Africa and Italy. He was on radio and Morse code. At the end of the War, he came home unscathed, which was wonderful. Only Jack Tenney from the village was killed.

Joyce vividly remembers when evacuee children from Margate came to live in the village in 1940, when she was about 13. She was at her Auntie Alice’s house when a bus stopped outside the Sunday School room opposite. Buses usually didn’t stop there. She can remember the little children, the boys in the short trousers they wore in those days, with their gas mask boxes around their necks. Inside the Sunday School Room were the women of the village, waiting to ‘pick out’ the child or children they wanted. She didn’t see what happened next because her Auntie pulled her away from the window, because it was rude to be nosy. As she was older than the evacuee children and she was at Senior School, she can’t really remember much more about them. Two girls, Jean Atkinson and Hilda Bruckman, stayed with Mrs Downing just a few doors away from where she lived, in the new council houses on Ridware Road. She remembers Mr King, who married three times. He and his wife, Ginny, were getting on a bit, but they took in an evacuee boy. Joyce thinks they were a bit frightening, especially Mrs King. The boy they took in was Bill Smith, Mildred’s brother, but he was too naughty for them and had to be billeted somewhere else. Mr Sherwood, who lived in Mavesyn House, was the billeting officer for the parish.

Sometime during the war, there was quite a lot of excitement when a bomb was dropped near the Tollgate at the High Bridge, where her Auntie Louisa lived. In her mind she said she can see exactly where the crater was, but other people have a different memory. Her father took her to see it. She thought that they went down the main road past the Tollgate, turning right into the field near the river, although her Auntie said it was on the same side of the road as the Tollgate and they were lucky to have been missed.

Italian prisoners of war were kept at Ridware Hall and were supervised by army officers. The Italians seemed nice, as of course they were just like our soldiers who were prisoners of war in Germany. They were here to help with agriculture on the farms, because many of our men were away fighting, so they were allowed out during the day and able to cycle around the area to where they worked. They were befriended by the children, probably because these men would give us treats from their rations, or because of the little gifts they made us fashioned out of everyday rubbish: jewellery or dolls and cars.

One year a baby was born to one of the travelling fairground families, but died very soon after. Joyce’s father, Mr Harry Knight, felt sorry that no one attended the grave, so he used to go and mow the grass and keep it tidy. Not so long ago a cross was put to mark the grave and, even more recently, a headstone has been erected. Mark Eades believes that a relative was responsible. The headstone reads:

Jaqueline Frances Fox

Born December 1943. Died February 1944

At 14, Joyce left school and her first job was looking after two children at Manor Farm, Mavesyn Ridware, owned by Jack and Connie Neighbour. They had two children, a little girl about 15 months old and another little girl. She worked from 7.30 a.m. to about 6.30 p.m., six and a half days a week. As well as looking after the children – getting them up and putting them to bed, feeding them and walking with them – she also had to do their washing and ironing. She wasn’t a nanny as such, but she did everything for them. There was also a maid named Gladys. For this she was given all her food and paid seven and sixpence. She still lived at home and just walked down the lane to work. On her half day off she would catch the bus to Rugeley, where she went to learn shorthand and typing.

During the Second World War the trade union of the Association of Engineering and Shipbuilding Draughtsmen moved its headquarters from London to Mansfield House in Rugeley. The shorthand and typing certificates Joyce now had paid off and she went to work in their offices, cycling to work every day. After the war the trade union returned to London. Her next job was in the Lichfield Laundry, working in the complaints department as a shorthand typist. She cycled to Handsacre and then got a lift to Lichfield. Just before her mother died in 1950, she went to work in the offices at Edward Johns Sanitary Ware, Armitage. We know it better as Armitage Shanks (it is now Ideal Standard). There she was an Emidicta [Dictaphone] typist.

When she was about 23 she went on her first holiday abroad – not something many local girls would have done. She and three friends, Land Army girls, went to Le Touquet in France. She remembers how war ravaged the town was. Talking about the war reminded Joyce about the Tollgate House at the High Bridge. Her Knight grandparents and their children lived there. Joyce said that as there was no bus from Hamstall Ridware, the men would ride on their bicycles and park them at the Tollgate to walk to Handsacre where they could catch a bus to their place of work. Later, after her grandparents had died, and her Aunt Louisa married Reginald Littler, she opened a little café there for passing cyclists. This was possibly in the 1960s.

Joyce married Harry Hancock in 1953. Harry and Joyce continued to live with her father Frederick, and she continued to work until her son Clive was born when she was 27. Harry was 13 years older than Joyce. He was a postman, working in Hill Ridware and also Stafford. Again, he cycled to work. He had been born missing fingers on one hand, so during the War he worked at GEC Stafford, making ammunition, returning to his Post Office job afterwards. When her son Clive was four, and she was pregnant with Gary, her brother’s

wife left and Joyce offered to look after David and Paul, her two nephews. Joyce had another boy, Noel, and so she had five lads to look after. She can remember washing and ironing 19 shirts. She commented that this is why she is grey!

In 1953, there was quite some consternation locally when the reservoir at Blithfield was built. She said looking back it was quite funny, but some of the older villagers worried in case the dam burst and the village was flooded. It would have had to go up Blithbury Bank first! It also caused great excitement the day the Queen Mother came to open it. The school was closed; the teachers and some of the school children were invited to go. She remembers them with their Union Flags.

In 1958 Joyce joined the WI. The subscription cost three and six. According to the WI records, in November 1961, she was on tea duty with Miss Dutton. The subject of the meeting that night was films, and the competition was the best-dressed clothes peg.

Eventually Joyce and Harry moved to a house in Chadwick Crescent and she went to work as a dinner lady at the Henry Chadwick School. In 1977, after an evening out, Harry had a heart attack and died.

In the early 1970s, Joyce was the moving force in obtaining the ground at the bottom of School Lane for the first children’s playing fields and park in the village.

Joyce has a strong connection with the parish church. As a girl, she attended church regularly and was in the church choir. The first rector she remembers was Rev. Allison, who lived in the rectory at Rake End. Rectors always had maids ‘living in’, as did the Froggatts. Following Rev. Allinson came Rev. Pimblet. He had a car, at a time when there were very few cars in the village.

The village has grown enormously during her lifetime. When she was small, almost everyone was local and everyone knew everyone. It wasn’t until much later that people came into the village. Once new houses were built, they attracted people from outside the village. Very few village people had the money to afford the new houses.

For over 20 years she helped to arrange the church flowers, and produced the flower rota. It was through the church that she met her second husband, Islwyn. Mena Davies, the vicar’s wife, invited Joyce to the vicarage and it was there Joyce was introduced to Islwyn Hopkins. After they married, they enjoyed holidays together and socialising with their friends. They were often seen walking out together with their dog. When Islwyn was taken ill, Joyce took care of him and he died at home.

Joyce dropped out of the WI for a time, but in 2003, she joined again along with her friends Nona Carter and Doreen Carter. She is also a member of Ridware History Society and has been an invaluable source of information about village history.